When a generic drug company wants to bring a new product to market, they don’t need to run full clinical trials like the original brand did. Instead, they prove bioequivalence - that their version behaves the same way in the body as the brand-name drug. But here’s the catch: if the statistical analysis is off, the whole study fails. And failing a bioequivalence (BE) study isn’t just a delay - it’s a $2 million to $5 million loss. The biggest reason? Underpowered studies with wrong sample sizes.

Why Power and Sample Size Matter More Than You Think

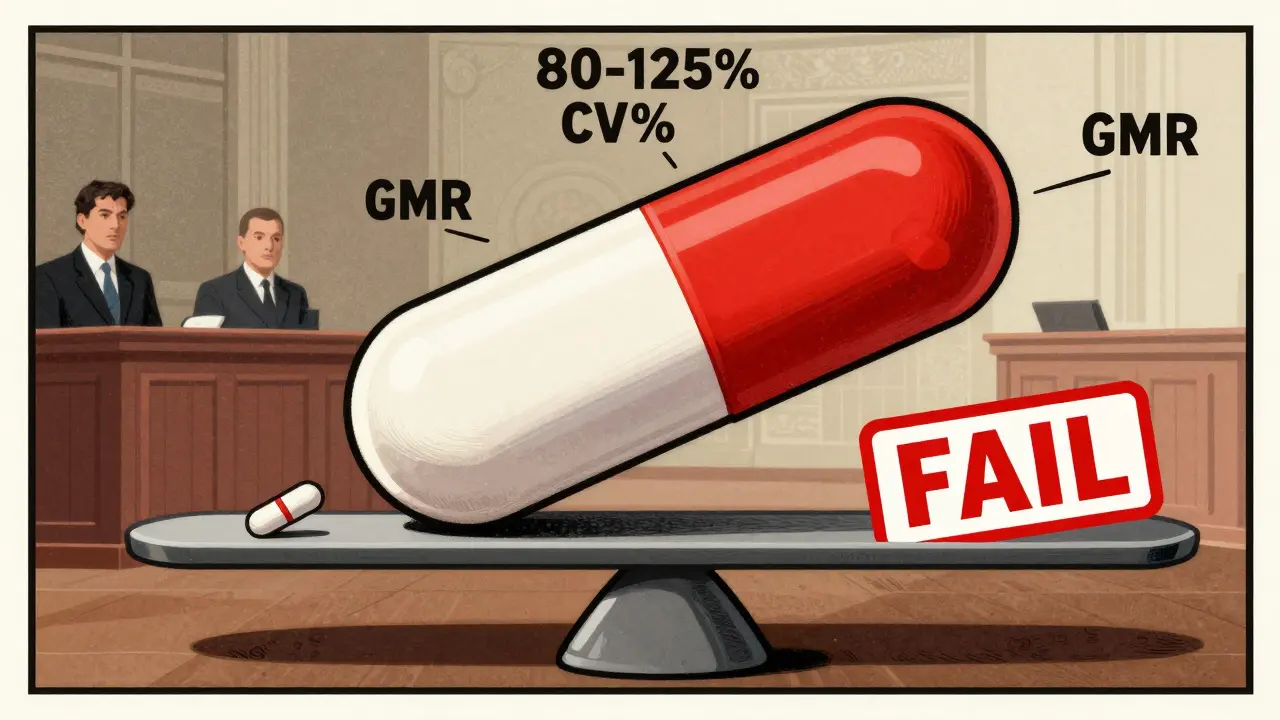

In a BE study, you’re not trying to prove one drug is better. You’re trying to prove it’s the same. That’s harder than it sounds. The FDA and EMA require the 90% confidence interval of the test-to-reference ratio (GMR) for both Cmax and AUC to fall entirely within 80-125%. If even one point of that interval spills outside, you fail. No second chances. No partial credit. Power is the chance you’ll correctly say two drugs are equivalent when they really are. Set it too low - say 70% - and you’re gambling. One in three studies will fail even if the drugs are identical. Industry standard? 80% or 90%. The EMA accepts 80%. The FDA often expects 90%, especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows like warfarin or levothyroxine. Don’t assume 80% is enough. Ask yourself: if your drug fails because of a 5% power gap, who pays?The Three Numbers That Decide Your Sample Size

You don’t guess sample size. You calculate it using three non-negotiable inputs:- Within-subject coefficient of variation (CV%) - This measures how much a person’s own drug levels bounce around from dose to dose. For most drugs, CV% is 10-30%. But for highly variable drugs (HVDs) like clopidogrel or valproic acid, it can hit 40-60%. If you use a literature CV of 20% when the real CV is 35%, your sample size will be too small by nearly 50%. The FDA found that 63% of sponsors underestimate CV% using published data alone.

- Expected geometric mean ratio (GMR) - This is your best guess of how the test drug’s exposure compares to the reference. Most assume 1.00 (perfect match). But real-world generics often land at 0.95 or 1.05. If you assume 1.00 but your actual GMR is 0.95, you’ll need 32% more subjects to reach the same power. Always plan for 0.95-1.05, never 1.00.

- Equivalence margins - Standard is 80-125%. But for Cmax in some cases, the EMA allows 75-133%. That small change can cut your sample size by 15-20%. Don’t assume all regulators use the same rules.

Use these numbers in the right formula. For a two-period crossover design, the sample size formula is:

N = 2 × (σ² × (Z₁₋α + Z₁₋β)²) / (ln(θ₁) - ln(GMR))²

Where σ is the within-subject standard deviation (calculated from CV%), Z values come from the normal distribution (1.96 for alpha=0.05, 1.28 for 80% power, 1.64 for 90% power), θ₁ is the lower limit (0.80), and GMR is your expected ratio.

But you don’t need to do this by hand. Tools like PASS 15, nQuery, or ClinCalc do it for you. Just plug in the numbers. The real skill? Knowing which numbers to plug in.

Real-World Examples: How CV% Changes Everything

Let’s say you’re testing a new generic tablet. Here’s what happens when you change just one variable:| Within-Subject CV% | Expected GMR | Target Power | Required Subjects (Crossover) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20% | 0.95 | 80% | 26 |

| 30% | 0.95 | 80% | 52 |

| 40% | 0.95 | 80% | 90 |

| 30% | 0.95 | 90% | 68 |

Notice how a 10% jump in CV% doubles your sample size? That’s why pilot studies matter. If you skip a small pilot and use a CV from a paper on a different formulation, you’re risking failure. Dr. Laszlo Endrenyi’s research shows 37% of BE study failures in oncology generics between 2015 and 2020 came from overly optimistic CV estimates.

Highly Variable Drugs? There’s a Shortcut

For drugs with CV% over 30%, the standard 80-125% range becomes impossible to hit without hundreds of subjects. That’s where reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE) comes in.Instead of fixed limits, RSABE widens the range based on how variable the reference drug is. For example, if the reference CV is 35%, the equivalence limits might stretch to 70-143%. This cuts sample sizes from 100+ down to 24-48. The FDA allows RSABE for drugs like warfarin, prasugrel, and certain antiepileptics. But you must prove the reference is highly variable - and you need regulatory pre-approval. Don’t assume you can use it. Submit a pre-submission meeting request first.

Dropouts, Multiple Endpoints, and Hidden Pitfalls

You calculated 52 subjects. Great. Now add 10-15% for dropouts. That’s 58-60. Why? Because if 5 people quit, your power drops from 80% to 72%. And you’ll be stuck explaining why you didn’t plan for it.Another trap? Testing both Cmax and AUC. Each has its own power. If you only power for Cmax (the more variable endpoint), your power for AUC drops by 5-10%. The American Statistical Association says you should calculate joint power - the chance you pass both endpoints. Only 45% of sponsors do this. Don’t be in the 55%.

Sequence effects in crossover designs also trip people up. If the order of drug administration (test first or reference first) influences results, your analysis must account for it. The EMA rejected 29% of BE studies in 2022 for ignoring sequence effects. Use washout periods of at least 7 half-lives. Document everything.

What the Regulators Actually Look For

The FDA’s 2022 Bioequivalence Review Template spells out exactly what they want in your statistical section:- Software name and version used (e.g., PASS 15, nQuery 9.2)

- All input parameters with justification (CV%, GMR, power, margins)

- How dropouts were accounted for

- Whether joint power for Cmax and AUC was calculated

- Whether RSABE was considered and why it was or wasn’t used

In 2021, 18% of statistical deficiencies in generic drug submissions were due to incomplete documentation. You can have perfect numbers - but if you don’t write them down clearly, regulators will assume you didn’t do the work.

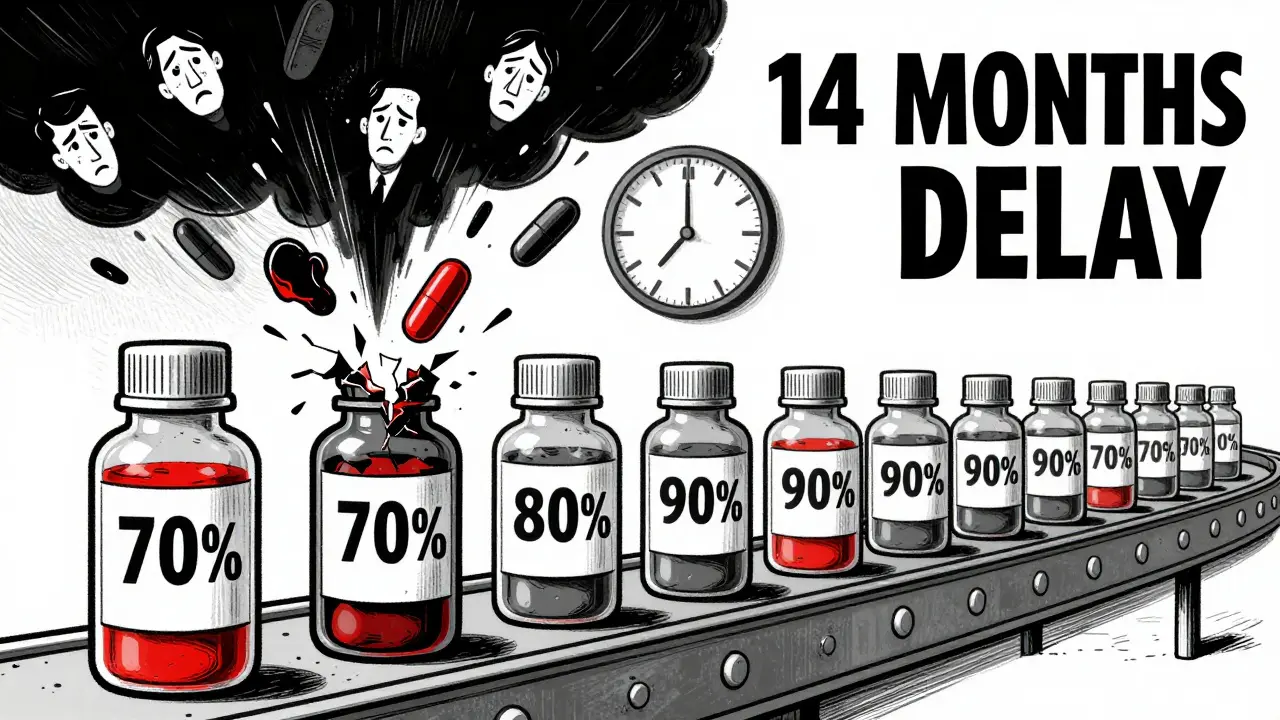

What Happens When You Get It Wrong

The FDA’s 2021 Annual Report showed 22% of Complete Response Letters cited inadequate sample size or power. That’s not a small number. It means over 1 in 5 generic applications get delayed because of statistics.One company spent $3.2 million on a BE study with 40 subjects, assuming a 25% CV. The real CV was 42%. They failed. Had they done a pilot study with 12 subjects first, they’d have known. They’d have saved $2.5 million and 14 months.

Dr. Donald Schuirmann, a top BE statistician, calls underpowered studies “the most common statistical failure in generic drug development.” He’s not exaggerating. The cost isn’t just money. It’s delayed access to affordable medicine.

Best Practices: What the Experts Do

Here’s what works in real life:- Run a pilot study - Even 12-18 subjects gives you real CV% data. Don’t rely on literature.

- Use conservative estimates - If your pilot CV is 28%, plan for 32%. Better to overestimate than fail.

- Calculate joint power - Power for Cmax and AUC together, not separately.

- Document everything - Save your software output. Include input values. Write down why you chose each number.

- Use regulatory-approved tools - PASS 15 and nQuery are industry standard. Free online calculators? Use them for rough estimates only.

- Plan for dropouts - Add 10-15%. Always.

The future? Model-informed bioequivalence. Using population pharmacokinetic models to reduce sample sizes by 30-50%. But as of 2023, only 5% of submissions use it. Regulatory uncertainty keeps it rare. Stick to the proven methods - for now.

Final Thought: Power Isn’t a Number - It’s a Commitment

Sample size isn’t about saving money. It’s about reliability. Every subject you enroll is someone who gave their time, their blood, their trust. If you underpower the study, you’re asking them to risk their health for a result that might be meaningless.Get the power right. Get the sample size right. It’s not just what regulators demand. It’s what patients deserve.

What is the minimum power required for a bioequivalence study?

Most regulatory agencies accept 80% power as the minimum. However, the FDA often expects 90% power, especially for narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine. Always confirm the target power with the specific regulatory body you’re submitting to. Never assume 80% is enough unless explicitly allowed.

How do I find the right coefficient of variation (CV%) for my drug?

Never rely solely on published literature. The FDA found that literature-based CV% values underestimate true variability by 5-8 percentage points in 63% of cases. Run a small pilot study with 12-18 healthy volunteers to measure within-subject CV% for Cmax and AUC. Use the higher of the two values for your sample size calculation. Conservative estimates prevent costly failures.

Can I use a sample size calculator from the internet?

Free online calculators can give you a rough estimate, but they often lack regulatory-specific features like RSABE, joint power calculation, or dropout adjustments. For submissions to the FDA or EMA, use validated software like PASS 15, nQuery, or FARTSSIE. These tools include regulatory guidelines built into their algorithms. Always document the software name and version in your protocol.

What is RSABE and when should I use it?

Reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE) is a method used for highly variable drugs (CV% > 30%) where the standard 80-125% equivalence range is too narrow. RSABE widens the acceptance range based on the reference drug’s variability, reducing required sample sizes from over 100 to 24-48. You must prove the reference drug is highly variable and get regulatory pre-approval before using RSABE. It’s not a shortcut - it’s a regulated alternative.

Why do I need to account for dropouts in my sample size?

If participants drop out, your effective sample size shrinks, and your statistical power drops. For example, if you plan for 52 subjects with 80% power and 10% drop out, your power falls to around 72%. That’s below the regulatory minimum. Always add 10-15% to your calculated sample size to ensure you still have enough subjects after dropouts. This is non-negotiable.

Do I need to power for both Cmax and AUC separately?

No. You need joint power - the probability that both Cmax and AUC pass bioequivalence simultaneously. If you only power for the more variable parameter (usually Cmax), your chance of passing both drops by 5-10%. The American Statistical Association recommends calculating joint power, but only 45% of sponsors do. Don’t be in the majority that’s underpowered.

What happens if my BE study fails due to sample size?

A failed BE study due to inadequate power means you must repeat the entire trial - with a larger sample size. This can cost $2-5 million and delay market entry by 12-18 months. The FDA cited inadequate sample size in 22% of Complete Response Letters in 2021. There’s no appeal. No partial credit. The only fix is a better design - and that starts with getting the power calculation right the first time.

sakshi nagpal

December 24, 2025 AT 13:48Wow, this is one of the clearest breakdowns of BE study power I’ve ever read. As someone from India working in generic pharma, I’ve seen too many teams cut corners on CV estimates just to save time. That 63% FDA stat about underestimating variability? Real. We ran a pilot last year with 15 subjects and saved $1.8M by adjusting sample size upfront. Pilot studies aren’t optional-they’re insurance.

Sandeep Jain

December 25, 2025 AT 12:43tho i just used an online calc for my last study… no joke it worked? but now im paranoid 😅

Sophia Daniels

December 27, 2025 AT 06:46Oh honey. You think this is bad? I had a client last year who used a 20% CV from a 2010 paper on a different salt form. They showed up with 38 subjects. FDA came back with a 14-page letter asking if they’d ever heard of ‘variability.’ They lost $4.2M and their lead statistician quit to open a taco truck. Don’t be that person. Use PASS. Document everything. Or don’t. Just know you’re gambling with patients’ access to medicine. 😒

Brittany Fuhs

December 28, 2025 AT 14:34It is rather disconcerting to observe the cavalier attitude toward statistical rigor in contemporary pharmaceutical development. One must question the intellectual integrity of those who rely upon unvalidated calculators or anecdotal literature. The FDA’s 2022 template is explicit. Compliance is not negotiable. It is a professional obligation.

roger dalomba

December 29, 2025 AT 15:31So… you’re telling me I can’t just wing it with Excel and a prayer?

Nikki Brown

December 30, 2025 AT 11:11My heart breaks for the patients who get stuck waiting because someone didn’t do their homework. 😔 This isn’t just math-it’s ethics. If you’re cutting corners on power, you’re not just risking money-you’re risking lives. And if you think a 70% power study is ‘good enough,’ you shouldn’t be in this field. 🙄

Peter sullen

December 30, 2025 AT 14:14It is imperative to underscore the non-trivial nature of within-subject variability, particularly in the context of crossover designs. The geometric mean ratio, when coupled with the log-normal transformation of pharmacokinetic parameters, necessitates precise estimation of sigma-squared via the coefficient of variation. Failure to account for joint power-i.e., the multivariate probability of simultaneously achieving equivalence for both Cmax and AUC-constitutes a fundamental statistical oversight. I strongly recommend the use of nQuery v9.2 with the FDA’s reference-scaled algorithm enabled.

Steven Destiny

January 1, 2026 AT 04:39Listen. I don’t care if you’re from India or Iowa. If you’re using a free online calculator and calling it a day, you’re not a scientist-you’re a liability. I’ve seen studies fail because someone thought ‘close enough’ was good enough. That’s not just bad science. That’s dangerous. Get your tools right. Or get out.

Fabio Raphael

January 2, 2026 AT 18:47Just wondering-has anyone here tried using model-informed bioequivalence? I know it’s rare, but I’ve read some early papers where they reduced sample size by 40% using PK modeling. Is it just too new for regulators, or are people just scared to try?

Amy Lesleighter (Wales)

January 4, 2026 AT 09:59power isnt a number its a promise. if you skimp on sample size you're asking people to give blood for nothing. just sayin.

Becky Baker

January 5, 2026 AT 02:56US only? What about the rest of the world? EMA’s rules are way more chill. Why are we all acting like the FDA is God here?

Rajni Jain

January 6, 2026 AT 10:38thank you for this! i work in a small lab in delhi and we dont have access to PASS or nQuery. i just use R scripts based on the formula you shared. its scary but we do our best. if anyone has a free template they trust, plz share 😊

Natasha Sandra

January 6, 2026 AT 18:52YESSS this is why I always tell my team: ‘If it’s not documented, it didn’t happen.’ 📝✨ Also, pilot studies = free money saved. I’m so tired of seeing people cry after a failure like it was a surprise. No, sweetheart. It was predictable. 😘

Erwin Asilom

January 8, 2026 AT 18:26Excellent summary. I’d add one thing: sequence effects aren’t just a footnote. I reviewed a submission where the washout was only 5 half-lives. The Cmax results were skewed by carryover. EMA flagged it immediately. Always document washout duration-and measure it.

Sumler Luu

January 9, 2026 AT 21:14Just curious-has anyone here used RSABE for a drug with CV% > 40%? I’m working on one now and the regulator asked for a pre-submission. What’s the process like? Any tips?