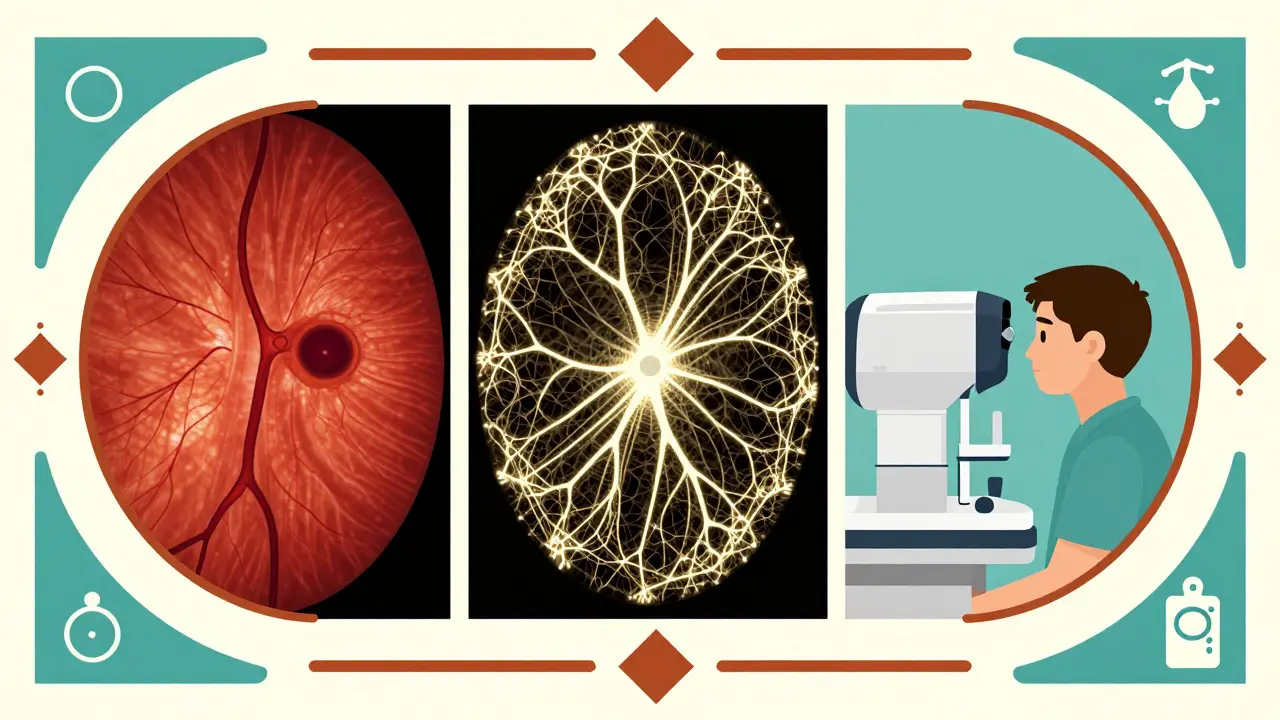

When your eye doctor says they need to take images of your retina, it’s not just a quick snapshot. Modern eye care relies on three key imaging tools: OCT, fundus photography, and angiography. Each one shows something different, and together they give a full picture of what’s happening inside your eye - especially when it comes to diseases like diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, or rare conditions like Coats disease.

What OCT Actually Shows

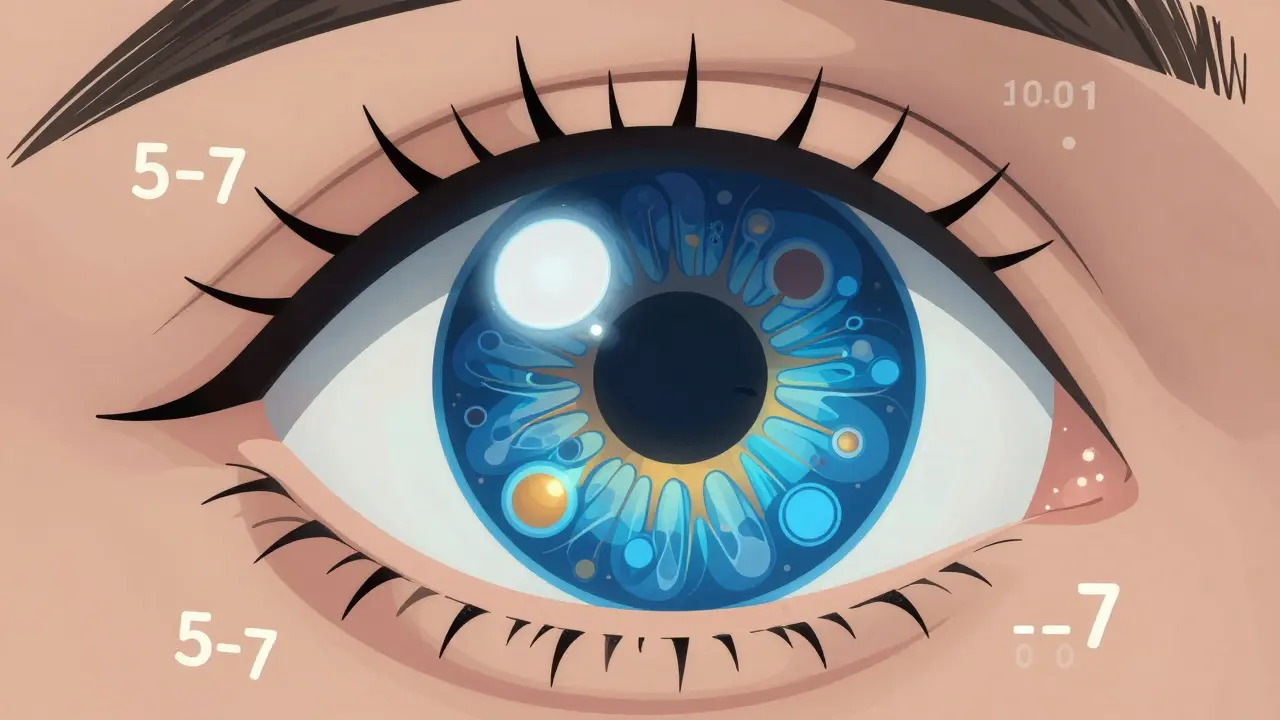

Optical Coherence Tomography, or OCT, is like an ultrasound for your eye - but instead of sound waves, it uses light. It creates detailed cross-sections of the retina, optic nerve, and layers beneath. Think of it as slicing open your eye in a digital 3D model, layer by layer. Spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) became the standard in the late 2000s. It captures images with a resolution of 5 to 7 micrometers - that’s finer than a human hair. This lets doctors see tiny fluid pockets, swelling, or thinning in the retina long before you notice vision changes. For example, in macular edema, OCT can detect fluid buildup under the fovea even if your vision still looks normal. Newer swept-source OCT (SS-OCT) machines are even faster, scanning up to 400,000 times per second. That means less motion blur, better images through cloudy lenses, and deeper views into the choroid - the blood vessel layer under the retina. In conditions like punctate inner choroidopathy (PIC), SS-OCT can reveal hidden inflammation or abnormal blood vessels that older machines might miss. But OCT doesn’t show blood flow. It shows structure. So if you have a leaky blood vessel, OCT might show fluid, but it won’t tell you where the leak is coming from. That’s where angiography steps in.Fundus Photography: The Baseline Snapshot

Fundus photography is the oldest of the three. It’s what most people picture when they think of an eye exam: a bright flash, a colorful image of the back of the eye, showing the optic nerve, blood vessels, and macula. Cameras like the Zeiss FF 450+ are commonly used in clinics to capture these images. It’s simple, fast, and non-invasive. No drops, no needles. It’s perfect for tracking changes over time. A diabetic patient might get a fundus photo every year. If a new spot appears near the macula, or if blood vessels start to look twisted, that’s a red flag. But fundus photos have limits. They’re two-dimensional. They can’t show depth. A swelling under the retina might look like a shadow, but you won’t know if it’s fluid, scar tissue, or a tumor. Also, if your pupil is small or your lens is cloudy from cataracts, the image quality drops. That’s why it’s rarely used alone anymore.Fluorescein Angiography: The Dye That Reveals Leaks

Fluorescein angiography (FA) is the only one here that requires an injection. A yellow dye called fluorescein is injected into a vein in your arm. As it circulates through your bloodstream, a special camera takes a series of photos, capturing how the dye moves through the retinal blood vessels. This is the gold standard for spotting leaks. In diabetic retinopathy, tiny vessels can burst and leak fluid. FA shows exactly where - whether it’s near the macula, around the optic nerve, or out in the periphery. It’s also the best way to see abnormal new blood vessels growing where they shouldn’t - a sign of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Studies show FA has higher sensitivity than OCT for detecting macular edema. One study found FA caught 100% of cases where OCT missed 21%. Why? Because OCT sees fluid, but FA sees the source: the leaky vessel. Sometimes, a vessel is leaking so mildly that no fluid pools yet - FA catches that early warning. But FA isn’t perfect. It’s invasive. Some people feel nauseous. Rarely, there’s an allergic reaction. The whole process takes 10 to 30 minutes. And because it’s a 2D image, it doesn’t show depth. You see the dye flow, but not whether it’s leaking into the inner layers or the outer ones.

OCT Angiography: The Dye-Free Revolution

OCT angiography (OCTA) is the newest player. It’s like OCT, but instead of just showing structure, it maps blood flow - without any dye. It works by detecting tiny movements of red blood cells. If blood is moving, the machine sees it. If not, it’s silent. This lets it create 3D maps of the capillary networks in the retina: the superficial layer, the middle layer, and the deep layer. You can see individual capillaries, how they branch, and where they stop. In diabetic retinopathy, OCTA can detect early signs of capillary dropout - areas where blood flow has shut down. These are often invisible on FA until they’ve grown large. In Coats disease, OCTA showed small, abnormal blood vessels hidden under exudates that fundus photos couldn’t capture. One major advantage? Speed. OCTA takes seconds. No waiting for dye to circulate. No risk of allergic reactions. Patients with poor vision or children who can’t sit still for 30 minutes can often get usable images. But OCTA has blind spots. It can’t show leakage. If a vessel is leaking fluid but not flowing abnormally, OCTA won’t see it. It’s also easily ruined by eye movement. A blink, a cough, or even a slight tremor can blur the image. And it’s still not great at visualizing the choroid - the deeper layer - unless you’re using SS-OCT.How They Work Together

No single tool tells the whole story. That’s why top retina clinics use them all - together. For diabetic retinopathy:- Fundus photo: tracks overall changes year to year.

- OCT: measures swelling, thickness, and structural damage.

- FA: finds active leaks and abnormal new vessels.

- OCTA: spots early capillary loss and hidden neovascularization.

- OCT: confirms drusen, fluid, or scar tissue.

- OCTA: shows choroidal neovascularization (CNV) without dye.

- FA: still needed if OCTA is unclear or if there’s bleeding obscuring the view.

- Fundus photo: documents the classic white exudates.

- OCT: reveals exudates in multiple retinal layers, subretinal fluid, and fibrotic nodules.

- OCTA: shows choriocapillaris non-perfusion - areas where blood flow has vanished, something FA often misses.

What’s Changing Right Now

The biggest shift? OCTA is becoming routine. Systems like the Spectralis OCTA have improved dramatically since 2020. Wide-field OCTA now covers more of the peripheral retina - areas previously only visible with FA. Studies show OCTA detects 57% more retinal capillary hemangiomas than older SD-OCT systems. But it’s not replacing FA yet. FA still wins for detecting subtle leakage in macular edema from vein occlusions. And FA remains the only way to see leakage patterns - like staining or pooling - that help guide treatment. Clinics are also starting to use AI to analyze OCT and OCTA images automatically. Software can now count capillary dropout, measure foveal avascular zone size, or flag areas of abnormal flow. This helps reduce human error and speeds up diagnosis.What Patients Should Know

If you’re getting these tests done:- OCT is painless. Just stare at a light for a few seconds.

- Fundus photography is quick and safe. Bright flash, no discomfort.

- Fluorescein angiography involves a needle. You might feel a warm flush, a metallic taste, or nausea. These pass quickly. Tell your doctor if you’ve ever had a reaction to dye.

- OCTA is like OCT - no needles, no dye. But you need to hold still. If you’re fidgety, ask for a shorter scan or a break.

What’s Next

The future is faster, wider, and smarter. Newer OCTA systems are already capturing the entire retina in one scan. Researchers are building normative databases - what normal looks like at different ages - so doctors can spot tiny deviations early. AI is being trained to predict which patients will progress to vision loss based on OCTA patterns alone. But the core truth hasn’t changed: eye disease is often silent until it’s advanced. These imaging tools are how we catch it before it’s too late.Is OCT better than fundus photography for detecting eye disease?

OCT gives detailed cross-sectional views of retinal layers, while fundus photography captures a flat, wide image of the back of the eye. OCT is better for spotting swelling, fluid, or thinning - like in macular edema or glaucoma. Fundus photos are better for tracking overall changes over time, like new blood vessels or pigment shifts. They’re not rivals - they’re partners.

Can OCT angiography replace fluorescein angiography completely?

Not yet. OCTA is excellent for visualizing blood flow without dye, and it’s great for detecting early capillary loss. But it can’t show leakage - the kind that causes fluid buildup in diabetic macular edema or vein occlusions. Fluorescein angiography still shows where and how much fluid is leaking. For now, they’re used together.

Is fluorescein angiography dangerous?

It’s very safe for most people. The dye is a mild contrast agent. About 1 in 100 people feel nauseous or have a brief flush. Severe allergic reactions are rare - less than 1 in 10,000. You’ll be asked about allergies before the test. If you’ve had a reaction before, your doctor may skip it or use an alternative.

Why do I need multiple scans if my vision is fine?

Many eye diseases - especially diabetic retinopathy and early macular degeneration - don’t affect vision until they’re advanced. These scans catch changes before you notice them. A small fluid pocket or a single blocked capillary might mean nothing today, but if it grows, it could cost you vision. That’s why early detection matters.

Can children get OCT and OCTA?

Yes, but it’s harder. OCT and OCTA require steady fixation - you have to stare at a light without blinking. Young children or those with developmental delays may need sedation or specialized equipment. Fundus photography is often easier for kids because it’s faster and doesn’t require as much focus.

AMIT JINDAL

February 8, 2026 AT 06:20Patrick Jarillon

February 8, 2026 AT 18:29Catherine Wybourne

February 9, 2026 AT 19:13Lakisha Sarbah

February 11, 2026 AT 13:51Ariel Edmisten

February 11, 2026 AT 14:39Niel Amstrong Stein

February 12, 2026 AT 02:18Paula Sa

February 13, 2026 AT 02:13Mary Carroll Allen

February 13, 2026 AT 02:36Joey Gianvincenzi

February 13, 2026 AT 07:19Jesse Lord

February 14, 2026 AT 17:05Amit Jain

February 15, 2026 AT 11:37