When a new drug hits the market, the job isn’t done. The FDA doesn’t just approve a medication and walk away. In fact, the real work often begins after approval. Clinical trials involve thousands of people over months or a few years. But once millions of patients start taking a drug daily - for years, sometimes decades - rare side effects, long-term risks, and unexpected interactions can show up. That’s where the FDA’s postmarket safety system steps in. It’s not a single tool. It’s a network of databases, technologies, regulations, and people working nonstop to catch problems before they hurt more people.

Spontaneous Reporting: The Foundation of Drug Safety

The backbone of the FDA’s system is the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Since 1969, this database has collected over 30 million reports of adverse reactions, medication errors, and product quality issues. These reports come from doctors, pharmacists, patients, and drug manufacturers. Anyone can submit a report through MedWatch, the FDA’s online portal. Healthcare providers submit about 63% of reports, patients only 6%. That gap matters. Many people don’t know how to report, or think their symptom isn’t serious enough. But even a single report can be the first clue to a larger problem. Manufacturers are legally required to report serious or unexpected side effects within 15 days. That’s faster than most countries. The FDA’s analysts don’t just read these reports - they run them through statistical filters. Tools like Empirical Bayes Screening (EBS) and Proportional Reporting Ratio (PRR) look for patterns. If a drug shows up in 10 times more reports of liver damage than expected based on similar drugs, that’s a signal. Not proof of danger, but a red flag that needs digging.Active Surveillance: Watching Millions in Real Time

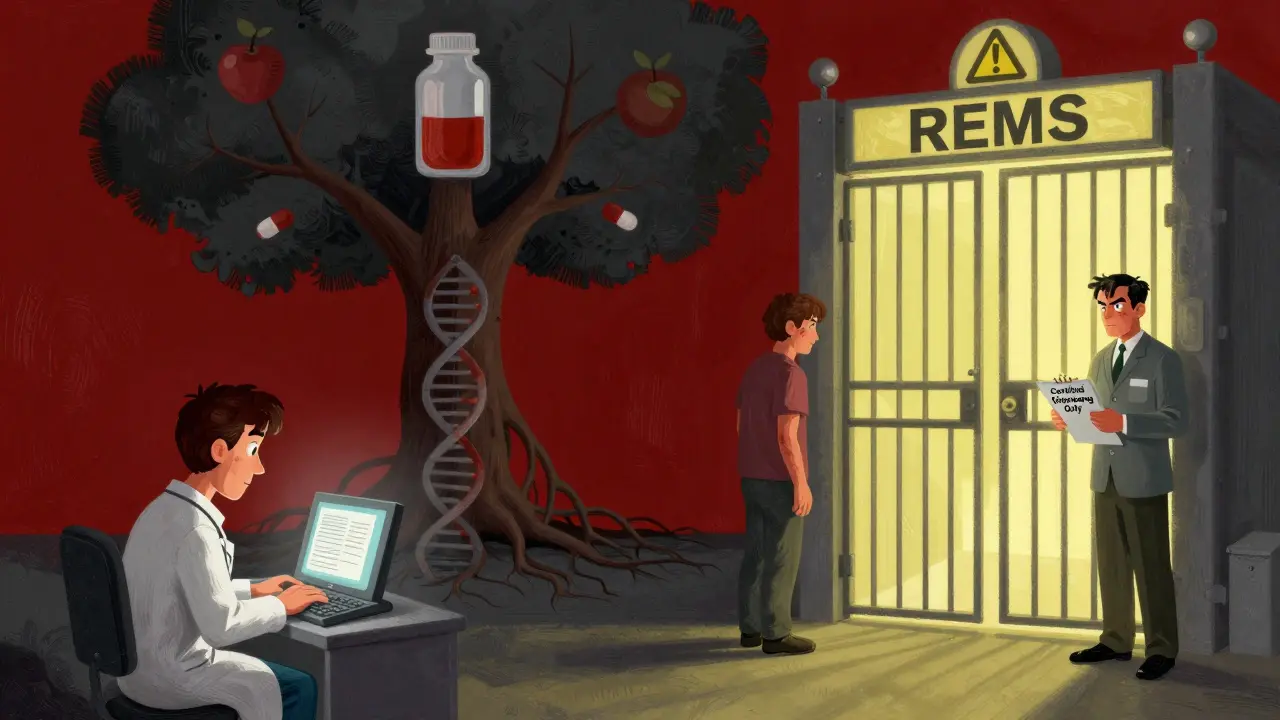

FAERS is passive. It waits for reports. But the FDA also runs Sentinel, an active surveillance system launched in 2008. Sentinel doesn’t wait. It pulls data from electronic health records, insurance claims, and pharmacy databases covering over 300 million people across the U.S. It’s like having a live feed from hospitals and clinics nationwide. Instead of waiting for someone to notice a problem and report it, Sentinel automatically scans for spikes in hospital visits, lab abnormalities, or deaths linked to specific drugs. For example, if a new diabetes drug suddenly shows up in 500 more kidney failure cases than usual over three months, Sentinel flags it. Then, epidemiologists and statisticians dig into the data to see if it’s real or just noise. This system cut detection time for serious safety signals from over a year to under seven months on average - thanks to new AI tools added in 2023.REMS: Controlling High-Risk Drugs

Not all drugs are created equal. Some carry serious risks - like liver failure, birth defects, or deadly blood clots. For these, the FDA requires a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). As of early 2024, 78 drugs had active REMS programs. These aren’t just warnings on the label. They can mean:- Only certified pharmacies can dispense the drug

- Patients must enroll in a registry and get regular blood tests

- Doctors must complete special training before prescribing

The Gaps: Underreporting and Slow Follow-Up

Despite its tools, the system has blind spots. Studies show spontaneous reporting catches only 1% to 10% of actual adverse events. Why? Patients don’t connect their new headache to a drug they started six months ago. Doctors are busy. Reporting takes time. A 2023 Reddit thread from an oncologist revealed she’d only submitted three reports in five years - even though she saw many side effects. The system relies on people to speak up. Another problem: delayed studies. The FDA can require drugmakers to run additional safety studies after approval - called postmarketing requirements. But a 2021 GAO report found that for nearly 4 out of 10 drugs approved between 2013 and 2017, those studies weren’t even started on time. Some took over three years past the deadline. That’s a long time to wait for answers about risks.Who’s Doing the Work?

Behind the scenes, the FDA’s Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology (OSE) has about 150 staff - medical officers, pharmacologists, data scientists, and statisticians. They review over 10,000 safety reports every year. They meet weekly to discuss signals. They consult with outside experts. They write guidance documents - 147 of them as of early 2024 - to help companies understand what’s expected. The FDA doesn’t do it alone. It partners with academic institutions, hospitals, and even other countries. But U.S. data is unmatched in scale. Sentinel covers 190 million covered lives - more than Europe’s EudraVigilance system. The FDA also uses a tool called InfoViP, which uses AI to scan thousands of reports for hidden patterns. Since 2018, it’s boosted signal detection by 27% and cut false alarms by 19%.

What’s Next? AI, Genomics, and Blockchain

The FDA isn’t standing still. In 2024, it launched Sentinel 2.0 - adding genomic data from 10 million people through partnerships with biobanks. That means scientists can now ask: Do people with a certain gene variant have higher risk of reaction to this drug? That’s personalized safety monitoring. A blockchain-based reporting pilot is coming in mid-2025. The idea? Make reports tamper-proof and traceable, so manufacturers can’t hide data. And by 2025, the FDA will require all high-risk drugs to have active surveillance plans - up from 68% in 2020. The biggest challenge? Growth. New therapies - gene therapies, cell treatments, complex biologics - are exploding. These drugs are powerful, but their long-term effects are unknown. The FDA’s system is effective, but it’s under pressure. Staffing is at 82% capacity. Funding hasn’t kept pace. As one expert put it: Without more resources, the system risks being overwhelmed.What You Can Do

You don’t have to be a doctor to help. If you or a loved one has an unexpected reaction to a medication - even something mild like a rash or dizziness - report it. Go to MedWatch. It takes 15 to 20 minutes. Your report could help someone else avoid harm. And if you’re a patient on a high-risk drug, ask your doctor: Is there a REMS program? What do I need to know? The FDA doesn’t have a crystal ball. But it has the most advanced drug safety system in the world. And it’s only getting smarter. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s protection. Every report, every data point, every algorithm is another layer between you and a hidden danger.How does the FDA know if a drug is unsafe after it’s approved?

The FDA uses two main methods: passive reporting through FAERS, where doctors, patients, and companies report side effects, and active surveillance through Sentinel, which scans health data from millions of patients to find patterns. If a drug shows up in unusually high numbers of reports for a specific side effect - like liver damage or heart rhythm issues - it triggers a deeper review. Experts then analyze whether the link is real or coincidental.

Are drug manufacturers required to report side effects?

Yes. Under FDA rules, drugmakers must report serious or unexpected adverse events within 15 days. They also submit detailed safety updates every 6 to 12 months. Failure to report can lead to fines, warning letters, or even product withdrawal. This legal requirement ensures companies can’t ignore safety signals - even if they’re inconvenient.

Why do so few patients report adverse reactions?

Many patients don’t realize their symptom is linked to a medication. Others think it’s too minor to report. Some don’t know how to report. A 2023 survey found only 6% of FAERS reports came from patients. The process feels disconnected from daily life. But even a single report can be critical. The FDA encourages patients to report anything unusual - especially if it’s new, severe, or happened after starting a drug.

What is a REMS program, and why does it matter?

A REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy) is a safety plan the FDA requires for drugs with serious risks. It can include special training for doctors, mandatory patient monitoring, or restricted distribution. For example, a drug that causes birth defects might only be available through certified pharmacies, and patients must confirm they’re not pregnant. REMS helps manage risks without taking a drug off the market entirely.

Can the FDA pull a drug off the market?

Yes. If a drug’s risks clearly outweigh its benefits and can’t be managed safely, the FDA can require the manufacturer to withdraw it. This has happened dozens of times - for drugs like Vioxx (heart risks), Rezulin (liver failure), and Fen-Phen (heart valve damage). The FDA doesn’t act lightly, but when evidence is strong and consistent, removing a drug is the last line of defense to protect public health.

Sarah Triphahn

January 14, 2026 AT 02:46People think the FDA is some superhero agency but honestly? It’s just a bunch of overworked clerks drowning in paperwork. I’ve seen reports get lost for years. That ‘active surveillance’? More like active denial. If it ain’t in the system, it didn’t happen. Classic bureaucracy.

And don’t get me started on manufacturers ‘reporting’ side effects. They bury the worst stuff under layers of jargon. I’ve read their submissions. It’s like reading a novel written by a lawyer who hates humans.

Vicky Zhang

January 15, 2026 AT 09:42I just want to say THANK YOU for writing this. As someone who’s been on five different meds over the last decade and had three weird reactions that no doctor could explain, I feel seen. I reported my rash after starting that new blood pressure pill - and no one ever called me back. But knowing there’s a system trying to listen? It means something. Please keep sharing this stuff. We need more awareness. Your work matters.

And if you’re reading this and you had a weird symptom after a new med? Go to MedWatch. Just do it. Even if it’s just a headache. You might save someone’s life.

Sarah -Jane Vincent

January 15, 2026 AT 11:08FAERS? Sentinel? REMS? LOL. This is all a distraction. The FDA is owned by Big Pharma. They let dangerous drugs through because they’re making billions. The ‘signals’? Fabricated noise. The real reason they don’t pull drugs faster is because they’re waiting for the stock price to drop so they can buy the company cheap.

And don’t tell me about ‘AI tools’ - AI is just a fancy word for ‘we still haven’t fixed the damn database from 1998.’ They’re using chatbots to filter reports now. That’s right. A bot decides if your kidney failure is ‘significant.’

Wake up. This isn’t safety. It’s PR.

Henry Sy

January 15, 2026 AT 11:29Man, I used to work at a pharmacy and let me tell you - the amount of BS we’d see… it’s unreal. People come in with their meds, eyes glazed over, muttering about ‘weird dreams’ or ‘tingling toes,’ and we just shrug. ‘Oh, that’s normal.’ But it ain’t. I saw a guy on statins who started seeing snakes. No joke. He didn’t report it. Thought he was losing it.

And yeah, the FDA’s got all these fancy systems, but half the docs I know don’t even know what FAERS stands for. It’s like having a fire alarm that only works if you know the code to hit ‘reset.’

Also, why do they call it ‘Spontaneous Reporting’? Like, is it magic? No. It’s just a system that assumes people have time, energy, and trust. We don’t. We’re tired. And scared.

Anna Hunger

January 16, 2026 AT 22:30While the intent of the FDA’s postmarket surveillance framework is commendable, the operational efficacy remains critically hampered by structural underfunding and inconsistent compliance among stakeholders. The disparity between regulatory mandates and real-world reporting behaviors - particularly among patient populations - reveals a profound disconnect between policy design and human behavior.

Moreover, the reliance on passive surveillance systems, such as FAERS, introduces significant ascertainment bias. The absence of mandatory, standardized reporting protocols for non-serious adverse events undermines the statistical validity of signal detection. It is imperative that the FDA institutionalize digital integration with EHRs at the point of prescribing to mitigate underreporting.

Jason Yan

January 16, 2026 AT 23:42I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately - not just as a patient, but as someone who’s watched my mom go through three different drugs for her autoimmune thing. The system feels like it’s trying, but it’s like a teacher who’s got 500 kids and only one red pen. They’re doing their best, but they’re drowning.

And honestly? I think the real hero here isn’t the algorithm or the database - it’s the patient who says, ‘Hey, this weird numbness started after I took this pill.’ That’s courage. That’s the quiet kind of activism nobody talks about.

Maybe the next step isn’t more tech. Maybe it’s just… reminding people that their voice matters. Even if it’s just one report. Even if it’s just a headache. It’s not noise. It’s a heartbeat.

shiv singh

January 18, 2026 AT 03:11USA thinks it’s the best? LOL. Look at Europe. They have better systems. They track everything. They don’t wait for people to die. They don’t let pharma lie. And now you want us to believe your ‘Sentinel’ is magic? Please. I’ve seen the data. The FDA approves drugs that got banned in Canada. They’re corrupt. They’re slow. They’re lazy.

And you think patients don’t report because they don’t know how? No. They don’t report because they don’t trust you. And why should they? You let thalidomide happen. You let Vioxx kill people. You’re not protecting us. You’re protecting profits.

Robert Way

January 19, 2026 AT 02:33so i just took this new anti depresant and my hand been tinglin for 2 weeks and i dont know if i should report it or not? like its not that bad but its weird? also i think the FDA is kinda cool but also kinda scary? like who are these people watching us? are they watching my pill bottle? lol

also i saw a guy on reddit say he got liver damage from a drug and the FDA didnt do anything for 8 months? is that true? i dont know what to believe anymore

Allison Deming

January 20, 2026 AT 14:17The assertion that patient reporting is ‘critical’ is both misleading and patronizing. The data demonstrates that patient-submitted reports are statistically insignificant in terms of signal detection and carry a high false-positive rate. The real value lies in structured, longitudinal data from electronic health records and claims databases - precisely what Sentinel provides.

Furthermore, the notion that ‘any report could save a life’ is emotionally compelling but epistemologically unsound. Without context, normalization, and statistical validation, anecdotal reports are noise - not evidence. The FDA’s reliance on AI and predictive modeling is not a failure of the system - it is its most robust evolution.

Susie Deer

January 20, 2026 AT 15:32USA still the best. No other country has this. Europe? They ban everything. China? They hide it. India? They sell fake pills. We got the most advanced system. You hate it? Move. We don’t need your complaints. We got 300 million people on Sentinel. You think your rash matters? It does. But we got bigger fish to fry. Keep reporting. Keep trusting. Keep American.

TooAfraid ToSay

January 21, 2026 AT 06:34Wait. So the FDA uses AI to find patterns in side effects… but the same people who run the system approved the drug in the first place? That’s like having the thief guard the bank. And now they want us to believe they’re not biased? Please. This is a circus. They need to be replaced. All of them. New people. No PhDs. Just regular folks who’ve been on meds.

Also - why is Sentinel only in the US? Why not global? Are they scared someone else will do it better? I smell a cover-up.

Dylan Livingston

January 23, 2026 AT 06:18Oh how darling. The FDA is ‘constantly improving.’ How quaint. Like a 19th-century doctor saying ‘we’ve upgraded from leeches to bloodletting with a new spoon.’

Genomic data? Blockchain? You’re not saving lives. You’re performing digital theater. The real issue? The FDA approves drugs based on trials that last six months on 3,000 people. Then they release them to 50 million. And you call that ‘science’?

I’ve seen the internal emails. The ‘red flags’ are ignored until the first lawsuit. That’s not safety. That’s liability management dressed in a lab coat.

Andrew Freeman

January 24, 2026 AT 01:52so like i read this whole thing and i think the FDA is kinda cool but also kinda sketchy? like why do they need blockchain? that sounds like crypto bs. and why are they only tracking 10 million people for genes? what about the other 320 million? also i think they should just make all drugs illegal and let people take weed instead

also i had a rash once and i didnt report it because i thought it was from my laundry detergent

says haze

January 25, 2026 AT 04:05It is not merely a question of infrastructure - it is a crisis of epistemic humility. The FDA operates under the illusion that quantification equals understanding. But biological systems are not linear. They are emergent, chaotic, deeply contextual. A spike in liver enzyme reports does not equate to causation - it merely signals correlation, which is the weakest form of knowledge.

And yet, we treat these algorithms as oracles. We outsource moral judgment to statistical models trained on flawed, incomplete, industry-filtered data. The real tragedy is not the underreporting - it is our collective surrender to technocratic certainty. We have replaced wisdom with widgets.

Alvin Bregman

January 25, 2026 AT 14:06hey i just wanted to say i really appreciate this post. i work in a clinic and we get a lot of patients on new meds and it’s hard to know what’s normal and what’s not. the fact that the FDA even tries to track this stuff means a lot. i know it’s not perfect but it’s better than nothing

also i think we should make reporting easier. like a one click thing in the patient portal. no forms. no logins. just tap and send. people are tired. they just want to feel heard

and hey if you’re reading this and you’re scared to report something - you’re not alone. just do it. even if it’s small. someone’s watching. and they care