Imagine getting sick every few weeks-not just a cold, but pneumonia, sinus infections, or stomach bugs that won’t go away. You take antibiotics, rest up, feel better for a bit, then it happens again. And again. After years of this, you finally get an answer: Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID). It’s not just bad luck. It’s your body’s immune system failing to make the antibodies that should protect you from everyday germs.

What Is CVID, Really?

CVID is one of the most common serious immune disorders you’ve probably never heard of. It’s not contagious. It’s not caused by stress or diet. It’s a genetic problem where your B cells-white blood cells meant to make antibodies-just don’t work right. You might have normal numbers of these cells, but they can’t turn into the antibody factories your body needs. The result? IgG, IgA, and often IgM levels crash. Normal IgG is 700-1600 mg/dL. In CVID, it’s often below 400 mg/dL. Some people have levels so low they’re almost undetectable.

This isn’t just about being prone to colds. Without enough antibodies, your body can’t fight off encapsulated bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae. These bugs are behind most of the serious lung and sinus infections CVID patients get. About 35% of pneumonia cases in CVID are linked to H. influenzae. Another 28% to S. pneumoniae. And because your immune system is so overwhelmed, infections become chronic. By age 50, 65% of people with CVID develop permanent lung damage from repeated infections.

Why Is Diagnosis So Hard?

Most people with CVID wait over eight years to get diagnosed. Why? Because the symptoms look like something else-chronic sinusitis, asthma, allergies, even irritable bowel syndrome. A 2023 survey by the Immune Deficiency Foundation found that 68% of patients saw three or more doctors before someone finally ordered the right blood tests.

The diagnosis isn’t just about low IgG. The European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) requires three things: IgG below 500 mg/dL, IgA below 7 mg/dL, and poor response to vaccines. If you got a tetanus or pneumococcal shot in the past and your body didn’t make protective antibodies, that’s a red flag. Genetic testing can help, but only 15-20% of cases have a known mutation. Genes like TACI, BAFF-R, and CD19 are often involved, but no single gene explains most cases. That’s why doctors still call it a syndrome-not one disease, but many.

What Happens Beyond Infections?

It’s not just about getting sick. CVID can turn your immune system against your own body. About 25% of patients develop autoimmune disorders. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), where your body destroys platelets, affects 15%. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), where red blood cells are attacked, hits 10%. Some develop rheumatoid-like arthritis. These aren’t side effects-they’re part of the disease.

Then there’s the gut. Around 30-50% of CVID patients have chronic digestive problems. Diarrhea, weight loss, bloating. Why? Because their immune system can’t clear parasites like Giardia lamblia. In the general population, giardia affects less than 1%. In CVID? It’s 12%. That’s not coincidence. It’s a direct result of lacking IgA, which normally lines the gut to block invaders.

And then there’s cancer. People with CVID have a 20-50 times higher risk of lymphoma. It’s not that CVID causes cancer-it’s that a broken immune system can’t spot and kill abnormal cells early. Granulomas (clumps of immune cells) can form in the lungs or liver, mimicking tuberculosis or sarcoidosis. These complications make CVID far more complex than just “low antibodies.”

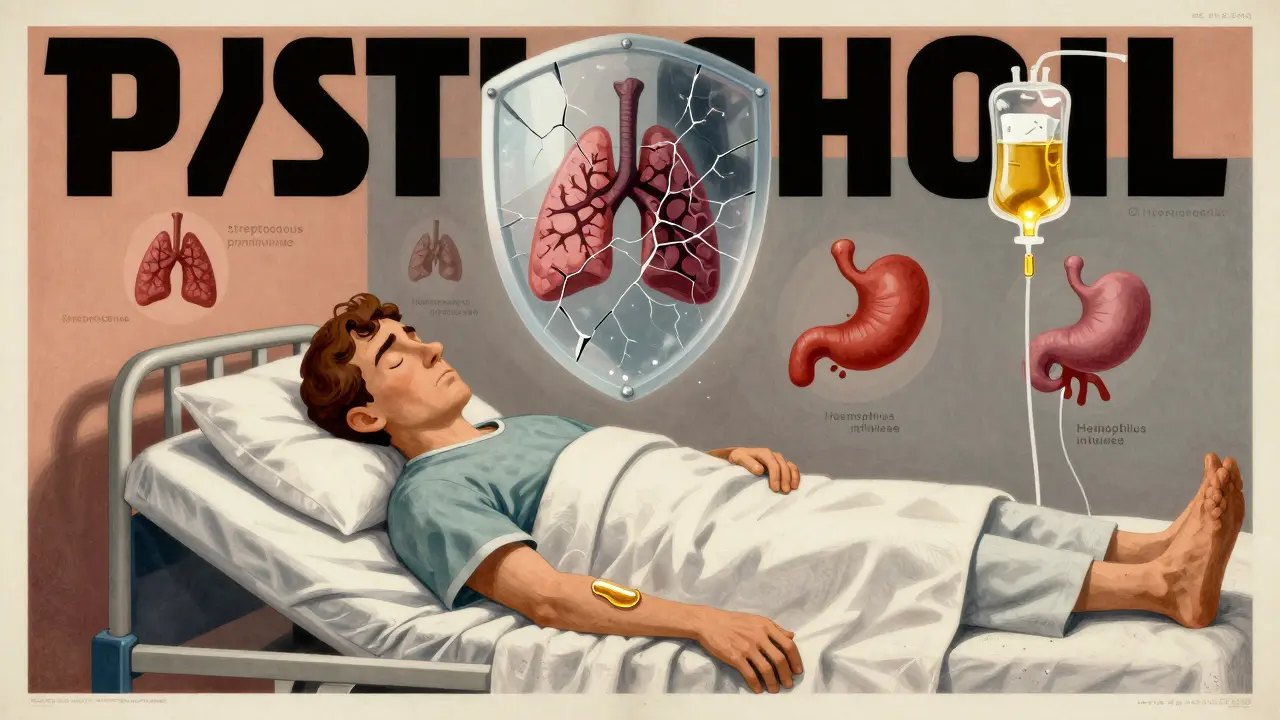

How Is It Treated? The Lifeline: Immunoglobulin Replacement

There’s no cure. But there is a treatment that changes everything: immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Since the 1980s, this has been the gold standard. It’s not a drug-it’s purified antibodies taken from thousands of healthy donors. You get them as an infusion, either through a vein (IVIG) or under the skin (SCIG).

IVIG is given every 3-4 weeks in a clinic. SCIG is done weekly at home, like insulin. Most people switch to SCIG once they learn how. Why? Fewer side effects. More control. Less time off work. A 2023 survey found 85% of SCIG users saw their infection rate drop from over 10 per year to under 3. Energy levels improved for 78% within three months.

Dosing is based on weight: 400-600 mg/kg monthly for IVIG, or 100-150 mg/kg weekly for SCIG. The goal? Keep your IgG level above 800 mg/dL. Below that, infections creep back. It takes most people 6-12 months to find the right dose and schedule. Some need more. Some need less. It’s personalized.

What Are the Side Effects?

IVIG can cause headaches (68% of reactions), chills, nausea, or fever. About 32% of people have infusion reactions. SCIG is gentler. The most common issue? Local swelling or redness at the injection site. Around 25-40% of SCIG users deal with this. The fix? Rotate sites. Slow down the infusion. Use smaller, more frequent doses. Most people adapt quickly-92% master home SCIG within eight weeks.

One thing no one talks about enough: cost. In the U.S., IVIG runs $65,000-$95,000 a year. SCIG? $70,000-$100,000. Insurance covers most, but not all. In low-income countries, only 35% of diagnosed patients get treatment. That’s not just a medical gap-it’s a life-or-death divide.

What’s on the Horizon?

Researchers are working on better options. One promising drug, atacicept, targets BAFF and APRIL-two proteins that mess up B cell signaling in CVID. A Phase III trial showed a 37% drop in severe infections compared to standard therapy alone. It’s not a replacement for immunoglobulin yet, but it could one day reduce how much you need.

Another big challenge? Plasma shortage. Immunoglobulin is made from donated plasma. Demand is outpacing supply. The Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association says there’s a 12% gap in 2023. That’s pushing prices up 15-20% each year. If this continues, access will get harder-even in rich countries.

Long-term, experts believe CVID isn’t one disease. It’s a group. Genomic testing is already splitting patients into subtypes. One might respond to biologics. Another might need a different approach. Within five years, treatment could be tailored, not one-size-fits-all.

Living With CVID

Life expectancy has doubled since the 1980s. Before immunoglobulin therapy, median survival was 33 years. Today? 59 years. And rising. With consistent treatment, many live into their 70s.

But it’s not easy. Chronic fatigue hits 74% of patients. Weight loss? 48%. Many struggle to gain weight, even eating high-calorie diets. It’s not laziness. It’s inflammation. It’s gut damage. It’s the constant toll of a body fighting a war no one else can see.

Support matters. The Immune Deficiency Foundation runs 200+ local groups and hosts annual conferences with 2,500+ attendees. Talking to others who get it? That’s medicine too.

Key Takeaways

- CVID is a genetic disorder causing low antibodies, not just low immunity.

- Diagnosis takes years on average-demand IgG, IgA, and vaccine response tests if you have recurrent infections.

- Immunoglobulin replacement (IVIG or SCIG) is life-saving and must be maintained long-term.

- Autoimmune diseases, gut infections, and lymphoma are common complications-not side effects.

- SCIG at home is often better tolerated and more convenient than clinic-based IVIG.

- Cost and plasma shortages threaten global access. Advocacy and awareness are critical.

Is CVID the same as having low IgG?

No. Many people have mildly low IgG without symptoms. CVID requires low IgG plus low IgA, poor vaccine response, and recurrent infections. It’s not just a number-it’s a pattern of illness and immune failure.

Can you outgrow CVID?

No. CVID is a lifelong condition. It’s not like a childhood allergy that fades. Once diagnosed, immunoglobulin therapy is needed indefinitely. Stopping treatment leads to rapid return of infections and complications.

Do vaccines work for people with CVID?

Most don’t. Because your B cells can’t respond, vaccines like flu, pneumococcal, or tetanus won’t trigger lasting protection. That’s why immunoglobulin therapy is essential-it gives you the antibodies your body can’t make. Live vaccines (like MMR or varicella) are also dangerous and avoided.

Is CVID hereditary?

Sometimes. About 10-20% of cases have a family history. But most have no known relatives with it. Even when genes are involved, inheritance isn’t simple. It’s not like cystic fibrosis-it’s complex, with multiple genes and environmental triggers playing a role.

Can you get CVID from an infection?

No. CVID is not caused by viruses, bacteria, or environmental exposure. It’s a genetic disorder of B cell development. You’re born with the tendency-it just takes years for symptoms to appear. It’s not contagious.

Next Steps if You Suspect CVID

- See an immunologist-not a general allergist or GP. They’re trained to recognize patterns.

- Ask for serum immunoglobulin levels (IgG, IgA, IgM) and vaccine response tests.

- Keep a detailed infection log: type, frequency, antibiotics used, hospitalizations.

- Join a patient registry (like the Immune Deficiency Foundation) to connect with experts and research.

- Start learning about SCIG. Many find it gives back control of their life.

Maddi Barnes

February 19, 2026 AT 15:27Hariom Sharma

February 19, 2026 AT 16:04Robert Shiu

February 19, 2026 AT 21:56Taylor Mead

February 20, 2026 AT 07:10Greg Scott

February 21, 2026 AT 12:12Benjamin Fox

February 23, 2026 AT 09:31Courtney Hain

February 24, 2026 AT 15:56Scott Dunne

February 26, 2026 AT 04:12Caleb Sciannella

February 26, 2026 AT 23:55Jeremy Williams

February 27, 2026 AT 04:00Nina Catherine

February 28, 2026 AT 10:48Amrit N

February 28, 2026 AT 13:22