Living with pheochromocytoma is a daily balancing act. This rare adrenal tumor constantly pumps out catecholamines, sending your heart rate and blood pressure into sudden spikes. When you add physical activity into the mix, the stakes get higher - but that doesn’t mean you have to quit moving altogether. Below you’ll find everything you need to know to stay active, stay safe, and keep the tumor under control.

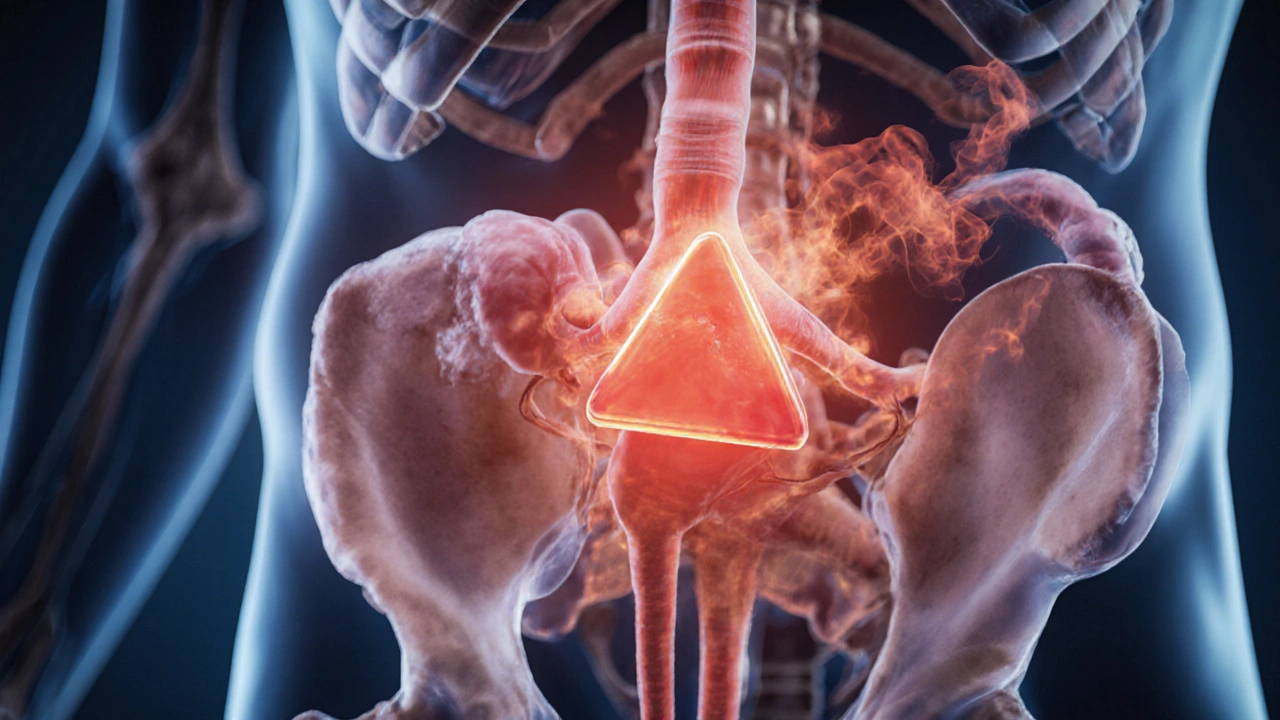

What Exactly Is Pheochromocytoma?

The adrenal gland is a small, triangular organ perched on top of each kidney. It produces hormones like adrenaline and noradrenaline, collectively called catecholamines. In pheochromocytoma a usually benign tumor that forms inside the adrenal medulla, causing an over‑release of catecholamines. The result? Sudden bouts of hypertension dangerously high blood pressure, palpitations, headaches, and excessive sweating. These symptoms can flare up without warning - even during routine chores.

Why Exercise Raises Concerns

Physical activity naturally increases heart rate and pushes blood vessels to work harder. For someone whose body already spikes catecholamines, that extra demand can trigger:

- Rapid rises in blood pressure - sometimes into hypertensive crisis territory.

- Irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias) that feel like a flutter or missed beat.

- Severe headaches or dizziness that could be mistaken for a typical workout fatigue.

Knowing these risks helps you plan a safe routine instead of avoiding exercise completely.

Medical Prep Before You Move

Before lacing up sneakers, get clearance from a healthcare professional familiar with pheochromocytoma. Here’s what they’ll typically review:

- Biochemical testing - plasma or urine metanephrines to gauge tumor activity.

- Imaging - CT or MRI scans confirming tumor size and location.

- Medication review - are you on an alpha‑blocker a drug that relaxes blood vessels and blunts catecholamine spikes? Many doctors add a beta‑blocker to control heart rate after alpha‑blockade is established before surgery or during active disease.

- Genetic testing - identify hereditary syndromes (MEN‑2, VHL, NF1) that may affect management and family screening.

- Blood pressure monitoring plan - a home cuff or wearable device to capture readings before, during, and after workouts.

Once you have a clear baseline and medication regimen, you can move forward with confidence.

Designing a Safe Exercise Program

The goal is to reap the cardiovascular and mental benefits of movement without triggering dangerous spikes. Follow these practical steps:

- Start low, go slow. Begin with light activities - walking, gentle yoga, or stationary cycling - at 40‑50% of your estimated maximum heart rate. Use the “talk test”: you should be able to speak full sentences without gasping.

- Warm‑up thoroughly. Spend 10‑15 minutes on low‑intensity movements (marching in place, arm circles). This gradual rise helps your body adjust to increasing catecholamine levels.

- Monitor vitals. Check blood pressure and heart rate before starting, midway, and after finishing. If systolic pressure climbs above 180mmHg or heart rate exceeds 120bpm, stop and rest.

- Choose steady‑state over interval. Continuous aerobic work (e.g., 30‑minute brisk walk) is generally safer than high‑intensity interval training (HIIT), which can cause abrupt catecholamine releases.

- Incorporate resistance training carefully. Use light weights (1‑2kg) or resistance bands, focusing on higher repetitions (15‑20) with longer rest periods (60‑90seconds). Avoid Valsalva maneuver (holding breath during lifts) - it spikes intra‑abdominal pressure and blood pressure.

- Stay hydrated and cool. Dehydration and overheating both amplify catecholamine effects.

- Cool‑down deliberately. End each session with 5‑10 minutes of gentle stretching and deep breathing to bring heart rate down gradually.

Below is a quick reference table that matches common exercise types with safety tips.

| Exercise Type | Intensity Recommendation | Key Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Walking / Light jogging | Low‑moderate (40‑55% HRmax) | Monitor BP every 5min; avoid hills at first |

| Stationary cycling | Low‑moderate; keep cadence steady | Seat height to prevent excessive core strain |

| Yoga / Pilates | Low; focus on breathing, avoid inverted poses | Skip breath‑holding sequences; stay upright |

| Resistance training (bands or light dumbbells) | Low‑to‑moderate; 15‑20 reps | Never hold breath; long rest intervals |

| High‑intensity interval training (HIIT) | Not recommended unless medically cleared | Risk of sudden catecholamine surge; consider alternative |

Red‑Flag Symptoms to Stop Immediately

Even with the best plan, you might encounter warning signs. If any of these appear, pause the activity, sit down, and check your vitals. If readings remain high or symptoms worsen, seek medical help right away.

- Sudden, severe headache that doesn’t ease with rest.

- Chest pain or pressure that feels out of proportion to effort.

- Rapid, pounding heartbeats (palpitations) that continue after stopping.

- Extreme dizziness, visual disturbances, or faintness.

- Sweating profusely without corresponding exertion.

Post‑Exercise Recovery Tips

Recovery is as important as the workout itself. Follow these habits to keep catecholamine levels stable:

- Drink at least 500ml of water within 30minutes of finishing.

- Eat a balanced snack containing protein and complex carbs (e.g., Greek yogurt with berries) to prevent blood sugar dips.

- Practice deep, diaphragmatic breathing for 5 minutes to activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Log your session - note duration, intensity, heart rate, and any symptoms. Sharing this log with your doctor helps fine‑tune medication doses.

When Surgery Changes the Game

If your tumor is removed, many of the catecholamine‑related concerns fade, but not instantly. Post‑operative patients still need to:

- Continue blood pressure monitoring for a few weeks as hormone levels normalize.

- Gradually increase activity intensity under medical guidance.

- Re‑evaluate medication - most alpha‑/beta‑blockers are tapered off after successful resection.

Even after cure, regular follow‑up imaging and biochemical testing are standard to catch any recurrence early.

Key Takeaways

- Exercise isn’t off‑limits; it just requires a tailored, low‑to‑moderate approach.

- Medical clearance, appropriate medication (alpha‑ and possibly beta‑blockers), and vigilant blood pressure monitoring are non‑negotiable.

- Steady‑state aerobic work, gentle resistance, and thorough warm‑up/cool‑down minimize spikes.

- Stop immediately if you experience headache, chest pain, palpitations, or dizziness.

- Post‑surgery, continue monitoring and ramp up activity gradually.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I run or jog with pheochromocytoma?

Running is possible, but keep it at a low‑moderate pace (under 55% of your max heart rate) and constantly monitor blood pressure. Begin with short intervals (5‑10minutes) and increase gradually only if vitals stay stable.

Do I need to stop all strength training?

No, but stick to light loads, high repetitions, and avoid breath‑holding. Resistance bands are a great starter because they provide tension without heavy weight.

How often should I check my blood pressure on workout days?

Measure before you start, halfway through (or every 5minutes for longer sessions), and after the cool‑down. Keep a log so your doctor can see trends.

Is it safe to do high‑intensity intervals once a month?

Only if your specialist explicitly approves it and you’re on optimal medication. Even then, start with very short bursts (15‑20seconds) and watch for any spike in symptoms.

Will my medication regimen change after tumor removal?

Most patients taper off alpha‑ and beta‑blockers within weeks to months post‑surgery, but the exact schedule depends on your recovery and follow‑up lab results.

Aly Neumeister

October 7, 2025 AT 12:49I’ve been juggling a pheochromocytoma diagnosis for years, and let me tell you-getting into a workout routine felt like stepping onto a live wire!! The adrenaline spikes made my heart feel like a jackhammer, the blood pressure surged like a balloon about to pop, and every treadmill session turned into a high‑stakes gamble. I started with a 5‑minute walk, checking my vitals every minute, and slowly the fear faded; the body learns to adapt, but only if you give it the chance to breathe.

joni darmawan

October 14, 2025 AT 11:29Observing the delicate balance required here, one might reflect on the broader metaphor: the body, like a finely tuned instrument, responds to both the gentle caress of movement and the abrupt shock of excess catecholamines. It is essential, therefore, to approach exercise with a measured humility, acknowledging the limits imposed by pathology while still honoring the innate drive toward vitality.

Richard Gerhart

October 21, 2025 AT 10:09From a clinical perspective, the first step is to verify that your medication regimen is optimized; alpha‑blockers should be established before introducing any beta‑blockade, as this prevents unopposed alpha stimulation. Once the pharmacologic baseline is secure, schedule a low‑intensity activity such as walking, aiming for a target heart rate not exceeding 55% of the predicted maximum. Begin each session with a 10‑minute warm‑up consisting of marching in place, arm circles, and gentle stretches, allowing catecholamine release to rise gradually. During the first ten minutes, monitor blood pressure every two minutes; if systolic pressure climbs above 180 mmHg, pause and assess. After the warm‑up, proceed to a steady‑state walk for 20‑30 minutes, maintaining a conversational pace-if you can speak full sentences without breathlessness, you are likely within a safe zone. Carry a validated home cuff or a reliable wearable device, recording readings before, midway, and after the activity; this data forms a valuable log for your endocrinologist. Hydration is critical: sip 250 ml of water every 15 minutes to avoid vasoconstriction triggered by dehydration. Should you feel a sudden headache, chest discomfort, or palpitations that persist beyond a minute, cease the exercise immediately, sit down, and re‑measure vitals; persistent abnormalities warrant urgent medical evaluation. Resistance training can be incorporated after two weeks of consistent cardio, using resistance bands or light dumbbells (no more than 2 kg), performing 15‑20 repetitions per set with a 60‑second rest interval; avoid the Valsalva maneuver at all costs. Post‑exercise, allocate five minutes to slow, diaphragmatic breathing to stimulate parasympathetic tone and assist in normalizing blood pressure. Finally, ensure that each session’s details-duration, intensity, heart rate, blood pressure, and any symptoms-are logged and reviewed with your healthcare team on a monthly basis to fine‑tune medication dosages and adjust activity levels as needed.

Kim M

October 28, 2025 AT 07:49🚨 Everyone talks about “medical clearance,” but have you considered that the pharma companies might be keeping the real risks hidden? 🙈 They want you on their meds, not on your own terms. Keep your eyes open, double‑check every lab result, and never trust a single source. 🕵️♀️

Martin Gilmore

November 4, 2025 AT 06:29Listen up, folks!!! This is not just some personal health tip – it’s a matter of national pride to stay fit under any condition!!! We must protect our bodies as we protect our borders, so follow the guidelines to the letter!!!

jana caylor

November 11, 2025 AT 05:09Great point! I think adding a short, 5‑minute meditation at the end of each session can really help lower that post‑exercise adrenaline surge. It’s a simple habit that anyone can adopt without extra equipment.

Vijendra Malhotra

November 18, 2025 AT 03:49In India we often use gentle yoga sequences that emphasize breathing; these are perfect for patients with pheochromocytoma because they keep the heart rate low while improving flexibility. Try a sun‑salutation flow without the more vigorous jumps.

Nilesh Barandwal

November 25, 2025 AT 02:29Never skip the cool‑down; it’s critical.

Elise Smit

December 2, 2025 AT 01:09As a coach, I always emphasize the three‑phase structure: warm‑up, active phase, and cool‑down. During the warm‑up, focus on dynamic movements that raise your core temperature without causing a spike-think leg swings, torso twists, and light marching. In the active phase, keep the intensity moderate; a brisk walk at 3‑4 mph is ideal, and you can incorporate low‑resistance cycling if you prefer a seated option. Monitor your heart rate using the talk test; if you can comfortably recite a short paragraph, you’re in the safe zone. After the main workout, spend at least five minutes transitioning back to rest with static stretches targeting the hamstrings, calves, and shoulders, coupled with deep diaphragmatic breaths. Hydration is a must-drink 500 ml of water within half an hour post‑exercise, and follow up with a protein‑rich snack to aid recovery. Finally, keep a detailed log of each session; over time you’ll notice patterns that can inform your doctor’s medication adjustments.

Sen Đá

December 8, 2025 AT 23:49While the recommendations are sound, I must stress the importance of avoiding any sudden posture changes that could trigger orthostatic hypotension, especially after the cooldown. Ensure you stand up slowly and re‑measure your blood pressure after a minute of standing.

LEE DM

December 15, 2025 AT 22:29Let’s remember that inclusivity matters even in exercise plans. If you have cultural preferences-like preferring group walks in community parks or using music from your heritage-integrate those elements; they boost motivation and keep you consistent.

mathokozo mbuzi

December 22, 2025 AT 21:09The systematic approach outlined here aligns well with evidence‑based practice, yet I would encourage further research into individualized heart‑rate zones based on genetic markers specific to pheochromocytoma patients.

Penny X

December 29, 2025 AT 19:49It is a moral imperative to recognize that neglecting to follow these safety protocols is not merely a personal oversight but a disregard for the sanctity of life itself. One must act with the utmost responsibility.

Amy Aims

January 5, 2026 AT 18:29Absolutely! 😊 Staying active while monitoring vitals is the gold standard; keep up the great work! 🙌

Shaik Basha

January 12, 2026 AT 17:09Yo, just tried the low‑intensity bike tip and felt legit good, no crazy spikes. Gonna keep it up, thanks!

Michael Ieradi

January 19, 2026 AT 15:49Indeed, recording data is essential; consistency matters.

Stephanie Zuidervliet

January 26, 2026 AT 14:29Honestly, these guidelines are just another set of boring rules; who wants to read a table of “do’s and don’ts” when you could just enjoy life?

Olivia Crowe

February 2, 2026 AT 13:09Even the simplest rule can be a lifesaver; don’t ignore it.

Aayush Shastri

February 9, 2026 AT 11:49Hey everyone! I’ve found that joining a local walking group not only provides accountability but also turns exercise into a social event, which makes sticking to the plan a lot more enjoyable.

Quinn S.

February 16, 2026 AT 10:29The preceding comment contains a misplaced infinitive; the phrase should read “to turn exercise into a social event,” not “to turn exercise into a social event.” Additionally, “sticking” requires a preposition: “sticking to the plan.” Please revise accordingly.