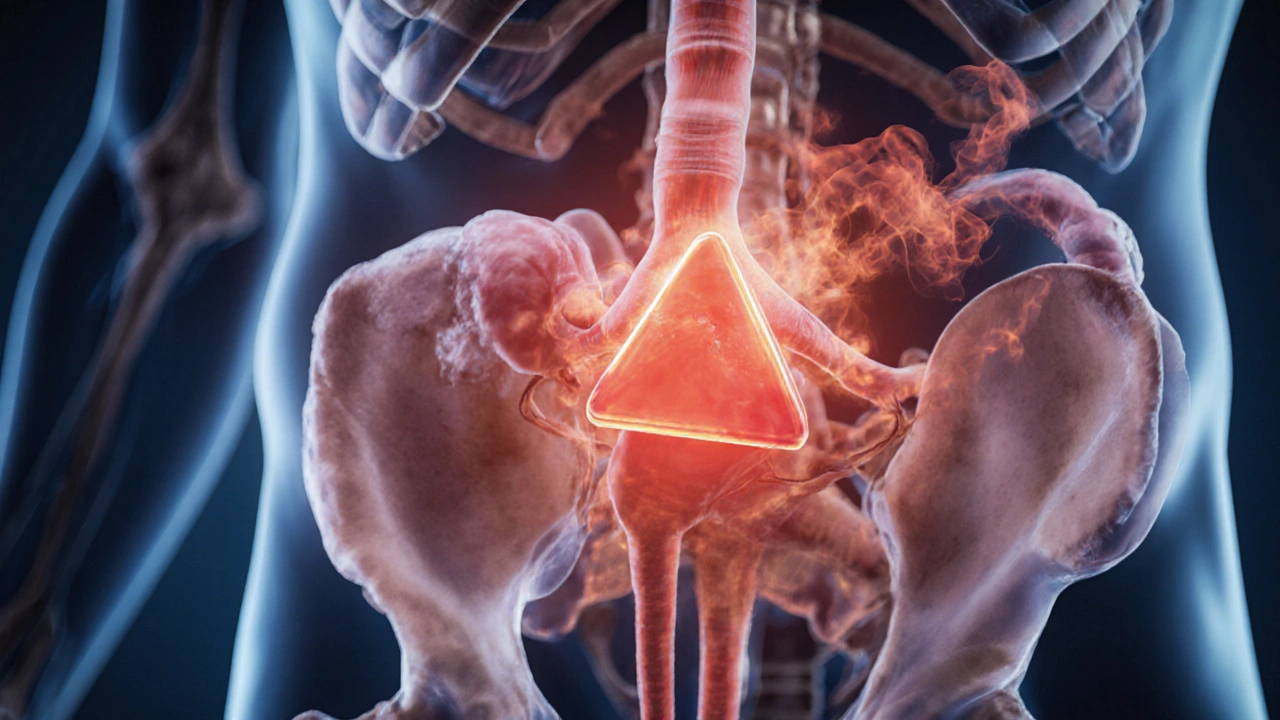

Adrenal Tumor: What It Is and Why It Matters

When talking about adrenal tumor, a growth that forms on the adrenal glands and can affect hormone production. Also known as adrenal neoplasm, it may be benign like an adenoma or malignant like adrenal carcinoma. The adrenal gland, a pair of small endocrine organs perched atop the kidneys produces cortisol, aldosterone and catecholamines, so any tumor can mess with those hormones. One common subtype is pheochromocytoma, a tumor that releases excess catecholamines causing spikes in blood pressure, while another is linked to Cushing's syndrome, a condition of cortisol over‑production resulting in weight gain, bruising and diabetes‑like symptoms. Understanding these connections helps you see why proper diagnosis matters.

Key Subtypes and Their Hormonal Footprint

Adrenal tumors break down into three main groups. First, adenomas are usually harmless and often discovered incidentally on imaging; they may secrete a mild excess of aldosterone, leading to low potassium and high blood pressure. Second, pheochromocytomas unleash norepinephrine and epinephrine, which trigger heart‑racing palpitations, sweating and headaches. Third, adrenocortical carcinomas are rare but aggressive, producing large amounts of cortisol or, less often, androgens, and they spread quickly if untreated. Each subtype influences the body in a distinct way, so the symptom pattern hints at the underlying tumor type.

Because hormones drive many of the signs, clinicians use lab tests to measure cortisol, aldosterone, metanephrines and testosterone. Elevated cortisol points toward Cushing's syndrome, while high metanephrines signal a pheochromocytoma. These biochemical clues are the first step before imaging. In fact, diagnostic imaging is the next logical move: a contrast‑enhanced CT scan can map the tumor’s size, shape and relationship to nearby vessels, while an MRI provides better detail for soft‑tissue invasion.

Imaging isn’t just about spotting the lump; it also informs treatment choices. Small, non‑functioning adenomas under 4 cm often require only monitoring, whereas tumors larger than that, especially if they secrete hormones, usually need surgical removal. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy is the gold‑standard for most benign lesions, but open surgery may be required for large or invasive adrenal carcinomas. For pheochromocytoma, patients must take alpha‑blockers before surgery to control blood pressure spikes.

Beyond surgery, targeted medications play a role when tumors can’t be removed. Mitotane is an adrenal‑specific chemotherapeutic agent used for metastatic adrenal carcinoma, while ketoconazole or metyrapone can lower cortisol in Cushing’s syndrome. For pheochromocytoma, beta‑blockers manage heart rate after alpha‑blockade. In the rare case of hereditary syndromes like MEN 2, genetic counseling and regular screening become essential because multiple endocrine tumors can arise.

Patients often wonder about lifestyle impact. Hormone excess can affect mood, sleep and metabolism, so a balanced diet low in sodium helps control aldosterone‑driven hypertension. Regular exercise improves cardiovascular health, which is crucial after a pheochromocytoma resection. Stress management techniques, such as mindfulness, can lessen cortisol spikes for those with Cushing’s‑related symptoms. While these tweaks don’t replace medical care, they support recovery and reduce recurrence risk.

Follow‑up care is a cornerstone of adrenal tumor management. After surgery, doctors routinely repeat hormone panels and imaging at six‑month intervals to catch any regrowth early. For malignant cases, oncologists may add radiotherapy or clinical trial drugs that target specific molecular pathways like IGF‑2. Long‑term monitoring also includes bone density checks, as chronic cortisol excess can weaken bones and lead to osteoporosis.

When adrenal tumors are discovered incidentally—often called “incidentalomas”—the decision tree hinges on size, imaging characteristics and hormone activity. If a lesion is under 1 cm and non‑functional, most specialists recommend annual CT scans for a few years. Larger or irregular masses raise red flags, prompting a full hormonal work‑up and possibly a surgical consult. This risk‑based approach prevents overtreatment while still catching dangerous tumors early.

Research is pushing the envelope on adrenal tumor detection. Newer PET tracers, like 68Ga‑DOTATATE, improve localization of pheochromocytomas, while liquid biopsies are exploring circulating tumor DNA to predict adrenal carcinoma behavior. These advances promise earlier diagnosis and more personalized therapy, meaning patients could avoid the side effects of broad‑spectrum chemotherapy.

Finally, it’s worth noting the psychological burden. A diagnosis of any tumor can spark anxiety, especially when hormone fluctuations affect mood and energy. Connecting with support groups, seeing a mental‑health professional, and staying informed about treatment options can lessen that weight. Knowledge empowers patients to ask the right questions during appointments.

Below you’ll find a curated collection of articles that dive deeper into each of these areas – from hormone‑specific symptoms and imaging tricks to surgery tips and post‑treatment care. Explore the posts to get practical guidance, real‑world examples and the latest updates that can help you or a loved one navigate an adrenal tumor diagnosis with confidence.

Pheochromocytoma & Exercise: Essential Safety Guidelines

Learn how to exercise safely with pheochromocytoma, covering medical prep, activity guidelines, red‑flag symptoms, and post‑surgery tips.

Read more