Steroid Psychosis Risk Calculator

Risk Assessment Tool

Use this tool to evaluate the risk of steroid-induced psychosis based on patient factors. This is particularly important when initiating high-dose steroids for conditions like lupus, asthma, or autoimmune disorders.

Risk Assessment Results

Continue monitoring but no immediate action needed. Check for early symptoms like restlessness or sleep disruption.

Enhanced monitoring required. Consider early intervention if symptoms develop. Review steroid dosing strategy.

Urgent action required. Steroid dose reduction may be necessary. Consult with psychiatric team immediately. Monitor for agitation or hallucinations.

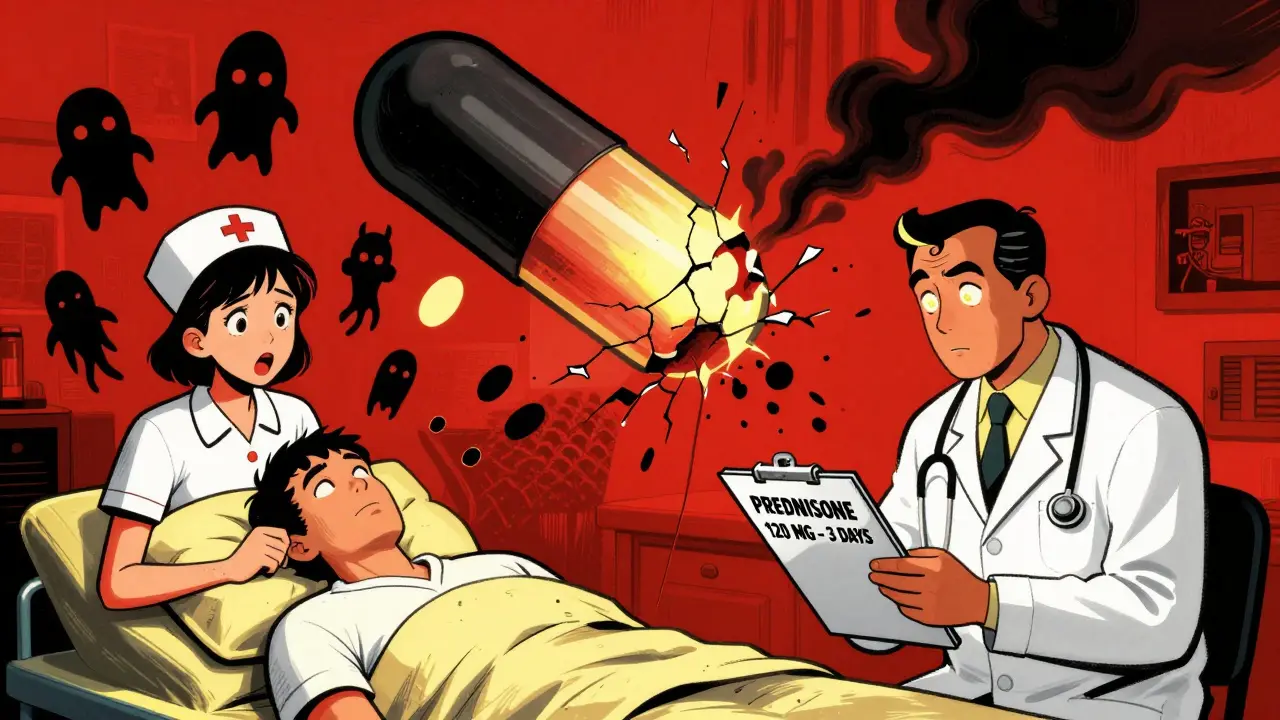

When someone starts a high dose of steroids - say, for a flare-up of lupus, asthma, or a severe autoimmune condition - most people expect side effects like weight gain, mood swings, or trouble sleeping. But few realize that steroid-induced psychosis can strike within days, turning a patient into someone unrecognizable: paranoid, hallucinating, or violently agitated. This isn’t rare. It happens in up to 6% of people on high-dose steroids, and in nearly 1 in 5 when the dose hits 80 mg of prednisone or more per day. If you’re in the emergency room and someone suddenly starts talking to invisible people or believes they’re being watched, you need to ask: When did they start their steroids? Because if you miss this, you could be treating a medical emergency like a mental illness - and it could cost them their safety, their health, or even their life.

What Exactly Is Steroid-Induced Psychosis?

Steroid-induced psychosis is a recognized medical condition under the DSM-5 as a substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder. That means it’s not schizophrenia. It’s not bipolar disorder. It’s not a random breakdown. It’s a direct biological reaction to corticosteroids - drugs like prednisone, methylprednisolone, or dexamethasone. The symptoms are real: hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren’t there), delusions (false, fixed beliefs), extreme agitation, or sudden mania. And it shows up fast - usually within the first 1 to 5 days after starting the medication.

It’s not just about high doses. Even moderate doses can trigger it in vulnerable people. A landmark study from the 1970s found that 4.6% of hospitalized patients on over 40 mg of prednisone daily developed psychiatric symptoms. Jump to 80 mg or more, and that number jumps to 18.4%. That’s not a fluke. That’s a pattern. And it’s not just psychosis. In a review of 79 cases, 40% had depression, 28% had mania, 14% had full psychosis, and 10% had delirium. The type of symptom often depends on how long the person has been on steroids: short-term users are more likely to swing into mania; long-term users tend to sink into depression.

Why Does This Happen?

It’s not magic. It’s biology. Corticosteroids mimic cortisol, your body’s natural stress hormone. But when you flood the system with synthetic versions, you throw off the whole balance. Your brain’s glucocorticoid receptors get overstimulated, while your natural cortisol production shuts down. This imbalance affects key brain areas involved in mood, perception, and decision-making - the same areas disrupted in Cushing’s syndrome and Addison’s disease. The result? Confusion, emotional instability, and sometimes, full-blown psychosis.

There’s still a lot we don’t know. We don’t yet have a simple blood test to predict who’s at risk. But we do know that people with a personal or family history of mood disorders, or those on long-term high-dose regimens, are more vulnerable. And while the exact brain pathways are still being mapped, one thing is clear: this isn’t a psychiatric failure. It’s a pharmacological accident.

How to Spot It Early - Before It Escalates

In the emergency department, time is everything. Waiting for someone to scream about aliens or try to jump out a window is too late. The real warning signs come before psychosis:

- Unexplained confusion or disorientation

- Restlessness or pacing

- Difficulty concentrating or following simple instructions

- Sudden irritability or aggression

- Sleep disruption - not just insomnia, but sleep that feels fragmented or unreal

These aren’t just "bad days." They’re red flags. If a patient started prednisone 3 days ago and now can’t remember what they had for breakfast, that’s not anxiety. That’s a neurological signal. Emergency staff need training to recognize this window - the 24 to 72 hours between the first signs and full psychosis. Catching it early means you can intervene before someone harms themselves or others.

Emergency Management: What to Do Right Now

When a patient presents with acute psychosis after steroid use, your first job isn’t to diagnose - it’s to keep them safe. Here’s the step-by-step protocol:

- De-escalate and secure the environment. Remove sharp objects, turn off loud noises, and have trained staff nearby. Physical restraints should be a last resort - they increase trauma and can worsen agitation.

- Check the steroid history. What drug? What dose? How long? A patient on 120 mg of prednisone for 4 days is at high risk. One on 10 mg for 6 weeks? Much lower risk.

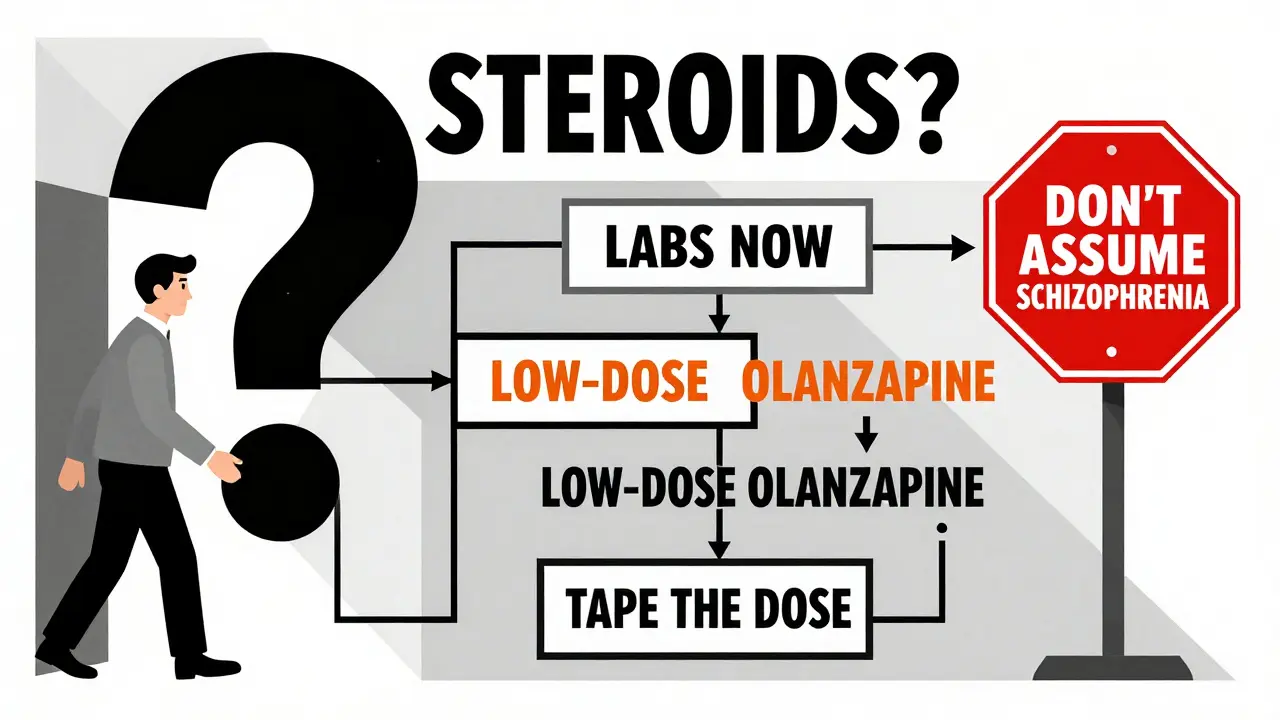

- Rule out mimics. Steroid psychosis can look like delirium from infection, low blood sugar, high blood sugar, or even a brain tumor. Run basic labs: glucose, electrolytes, kidney and liver function, CBC, and a urine drug screen. A simple blood sugar test can rule out hyperglycemia - a common steroid side effect that mimics psychosis.

- Start treatment - but don’t overdo it. This is where most ERs get it wrong.

Antipsychotics are necessary, but standard doses for schizophrenia are too high for steroid-induced psychosis. A 2022 survey found 61% of emergency doctors gave 20-30 mg of olanzapine - a dangerous overmedication. The correct starting dose? 2.5 to 5 mg of oral olanzapine, or 1 to 2 mg of risperidone. For noncompliant patients, use intramuscular olanzapine (10 mg) or haloperidol (2-5 mg). If you use haloperidol, give benztropine or diphenhydramine at the same time - it cuts the risk of painful muscle spasms by over 80%.

The Real Fix: Tapering the Steroid

Medication alone won’t cure this. The core treatment is reducing or stopping the steroid. In 92% of cases, symptoms fully resolve when the dose is lowered below 40 mg of prednisone (or 6 mg of dexamethasone). That’s not a guess - that’s from multiple clinical studies.

But here’s the catch: you can’t just stop steroids cold. If someone’s on them for organ transplant rejection or severe rheumatoid arthritis, sudden withdrawal can cause adrenal crisis, shock, or death. So tapering must be smart. Work with the prescribing doctor. Reduce the dose by 25-50% every 2-3 days, depending on the underlying condition. If the steroid is essential, keep it going - but add antipsychotics to manage symptoms while you plan a slow, safe reduction.

Lithium can help prevent mania, but it’s risky. It needs blood tests, kidney monitoring, and careful dosing. Only use it if you have psychiatric support. SSRIs, antidepressants, or seizure drugs like valproate? They’re sometimes tried, but the evidence is weak. Stick to what works: taper + low-dose antipsychotic.

What Not to Do

- Don’t assume it’s schizophrenia. You’re not helping if you lock someone into a long-term antipsychotic regimen for a condition that will vanish in days.

- Don’t ignore the steroid. If you treat the psychosis but leave the dose unchanged, symptoms will return - often worse.

- Don’t use high-dose antipsychotics. More isn’t better. It’s just more side effects: sedation, low blood pressure, movement disorders.

- Don’t delay lab tests. A simple glucose test can rule out a treatable mimic.

What’s Coming Next

There’s hope on the horizon. In 2021, the National Institutes of Mental Health launched a study tracking 500 people starting high-dose steroids, looking for genetic markers and early blood biomarkers that predict who’s likely to develop psychosis. Results are expected by late 2024. And by mid-2025, the American Psychiatric Association will roll out a clinical decision tool that tells doctors: "Based on this dose, age, and history, your patient has a 23% risk of psychosis - here’s how to adjust."

Right now, we’re flying blind. But we don’t have to. We know the triggers. We know the timeline. We know how to treat it. The problem isn’t lack of knowledge - it’s lack of routine. Too many ERs still treat steroid psychosis like any other psychotic break. That’s why 43% of emergency doctors don’t follow tapering guidelines. That’s why patients suffer longer than they should.

The fix is simple: make steroid psychosis part of your emergency protocol. Train your staff. Add a checklist to your intake form. Ask about steroids before you ask about family history. Because when someone comes in with a sudden, unexplained psychotic episode - and you find out they started prednisone three days ago - you don’t need a fancy scan. You just need to know what to do next.

Can steroid-induced psychosis happen with low doses?

Yes, though it’s rare. While high doses (over 40 mg prednisone daily) carry the highest risk, even low doses can trigger psychosis in people with a personal or family history of mood disorders. The key isn’t just the dose - it’s the person. If someone has had depression or mania before, their brain may react more strongly to the hormonal shift.

How long does steroid psychosis last?

Symptoms usually start improving within 3 to 7 days after lowering the steroid dose or starting antipsychotics. Full resolution typically happens in 2 to 6 weeks. In rare cases, symptoms linger for months - especially if the steroid wasn’t tapered properly or if the person had pre-existing mental health conditions.

Is steroid-induced psychosis the same as steroid-induced mania?

They’re on the same spectrum. Mania involves elevated mood, racing thoughts, decreased need for sleep, and impulsivity - without hallucinations or delusions. Psychosis includes those hallucinations and delusions. Many patients go from mania to psychosis as symptoms worsen. The treatment is similar: reduce the steroid and use antipsychotics. But mania is often easier to catch early.

Can you prevent steroid psychosis before it starts?

Not reliably - yet. But you can reduce risk. For high-risk patients (history of bipolar disorder, prior steroid psychosis, or high-dose regimens), consider starting with the lowest effective dose. Monitor mood closely in the first week. Some doctors now use low-dose lithium or valproate prophylactically, but this isn’t standard. The best prevention is awareness - knowing who’s vulnerable and watching for early signs like agitation or confusion.

What if the patient needs the steroid for life?

If the steroid is essential - like for transplant patients or severe autoimmune disease - you don’t stop it. You manage the psychosis with low-dose antipsychotics (olanzapine, risperidone) and monitor closely. Work with a liaison psychiatrist. Some patients stay on antipsychotics long-term while maintaining their steroid dose. The goal isn’t to eliminate the steroid - it’s to keep the person safe and functional.

Emergency teams who treat steroid-induced psychosis as a medical emergency - not a psychiatric one - see better outcomes, fewer rehospitalizations, and less trauma for patients. It’s not about being a psychiatrist. It’s about being a good clinician who asks the right question at the right time.

Sonja Stoces

February 12, 2026 AT 21:08Kristin Jarecki

February 13, 2026 AT 23:15Vamsi Krishna

February 15, 2026 AT 22:51christian jon

February 17, 2026 AT 18:57Pat Mun

February 18, 2026 AT 13:01Sophia Nelson

February 19, 2026 AT 13:37Steve DESTIVELLE

February 19, 2026 AT 13:59steve sunio

February 20, 2026 AT 18:52Gloria Ricky

February 21, 2026 AT 15:41Stacie Willhite

February 22, 2026 AT 17:13Jason Pascoe

February 23, 2026 AT 09:30Ojus Save

February 24, 2026 AT 23:41Alyssa Williams

February 26, 2026 AT 22:31Reggie McIntyre

February 28, 2026 AT 02:27