When you take a pill, injection, or cream, you expect it to work exactly as it should-every time. That’s not luck. It’s the result of strict stability testing under controlled temperature and time conditions. These tests aren’t optional. They’re the backbone of drug safety. If a medication degrades too fast, it could lose potency, turn toxic, or fail to treat your condition. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA don’t leave this to chance. They enforce global standards that spell out exactly how long drugs must be stored, at what temperature, and how often they’re tested.

Why Stability Testing Matters

Stability testing isn’t about checking if a drug looks right on the shelf. It’s about proving it stays safe and effective under real-world conditions. Think about a medicine sitting in a pharmacy in Melbourne, then shipped to a warehouse in Singapore, then delivered to a clinic in Nairobi. Each place has different heat and humidity. Without testing, you wouldn’t know if the drug breaks down before it reaches the patient.

The process started with ICH Q1A(R2), a guideline published in 2003 by the International Council for Harmonisation. It brought together regulators from the U.S., Europe, and Japan to agree on one set of rules. Before that, companies had to run separate tests for each region-wasting time, money, and resources. Now, one test can support global approval. But that doesn’t mean it’s simple.

Failure to meet these standards can mean recalls, warning letters, or even blocked product launches. In 2022 alone, the FDA issued 27 warning letters specifically for stability testing problems. One company had to pull 150,000 vials of a generic drug because it didn’t detect aggregation at 40°C. That’s not a small mistake. That’s a patient safety risk.

Temperature and Time: The Core Rules

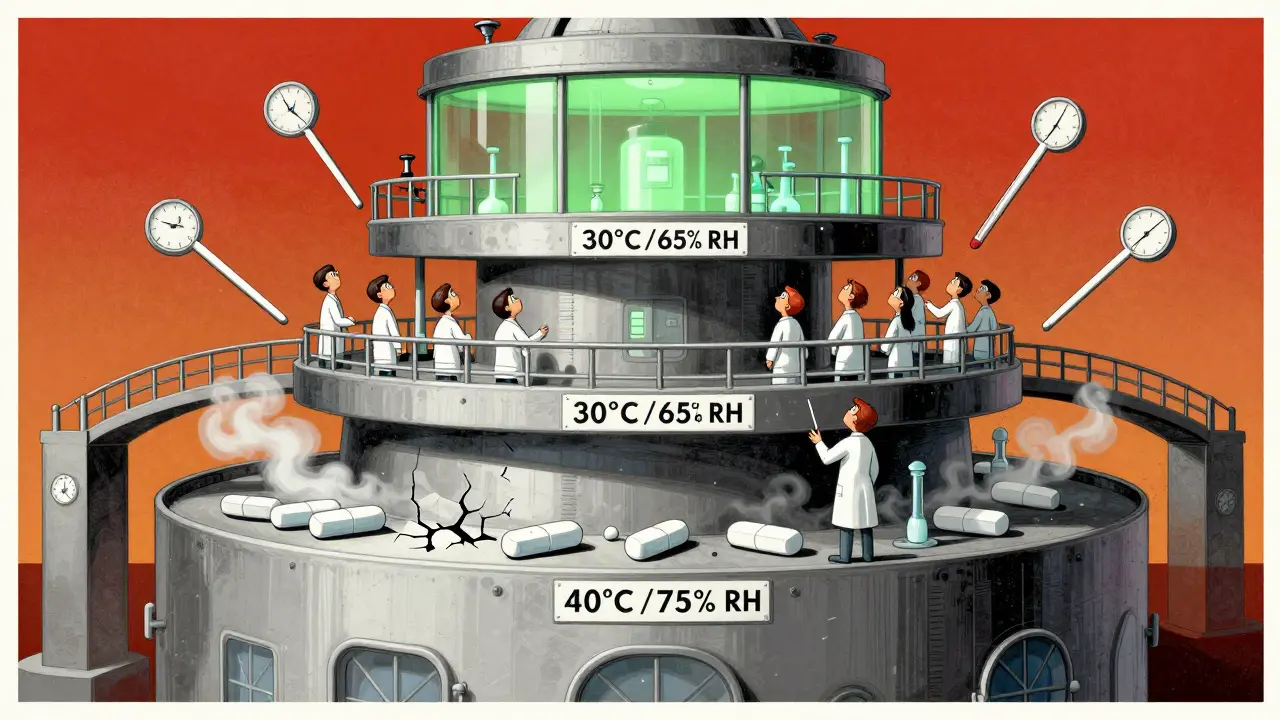

ICH Q1A(R2) defines three main testing conditions: long-term, accelerated, and intermediate. Each has exact numbers you can’t ignore.

- Long-term testing: This is the gold standard. It runs for up to 36 months. The two approved conditions are 25°C ± 2°C at 60% RH ± 5% RH or 30°C ± 2°C at 65% RH ± 5% RH. Which one you pick depends on where your product will be sold. If you’re targeting tropical markets, you go with 30°C. If you’re selling in Europe or Australia, 25°C is often enough.

- Accelerated testing: This is the stress test. You put the drug at 40°C ± 2°C and 75% RH ± 5% RH for six months. The idea? If the drug survives this harsh environment, it’s likely to last years under normal conditions. This test helps predict shelf life faster. But it’s not perfect. Some drugs-especially biologics or moisture-sensitive ones-break down in ways this test can’t predict.

- Intermediate testing: This one’s a backup. You run it at 30°C ± 2°C and 65% RH for six months, but only if your long-term test is done at 25°C and the accelerated test shows a problem. It’s not always required, but skipping it can cost you.

For refrigerated products, like insulin or some vaccines, the rules change. Long-term storage is at 5°C ± 3°C for 12 months. Accelerated testing? Not at 40°C. Instead, it’s done at 25°C ± 2°C and 60% RH for six months. Why? Because freezing and thawing are bigger threats than heat for these products.

Climatic Zones and Global Challenges

Not all countries have the same climate. ICH recognizes five global zones:

- Zone I (Temperate): 21°C / 45% RH

- Zone II (Subtropical): 25°C / 60% RH

- Zone III (Hot-Dry): 30°C / 35% RH

- Zone IVa (Hot-Humid): 30°C / 65% RH

- Zone IVb (Hot-Higher Humidity): 30°C / 75% RH

If your drug is meant for Zone IVb-think India, Brazil, or parts of Africa-you need to test at 30°C and 75% RH. But here’s the catch: most companies test at 25°C/60% RH because it’s cheaper and easier. That’s risky. A 2023 industry survey found that companies targeting Zone IV markets add 4-6 months to their development timelines just to adjust stability protocols. One drug passed testing in Europe but failed in Nigeria because humidity caused tablet crumbling. That’s not a manufacturing flaw. That’s a testing flaw.

How Often Do You Test?

Testing isn’t a one-time thing. You check the drug at specific intervals: 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months. Early time points (3, 6, 9 months) are critical. That’s when most degradation shows up. If a drug loses 5% potency by month 6, you know it won’t last 24 months. But if it holds steady, you can confidently say it’s good for 3 years.

Chambers must hold temperature within ±0.5°C and humidity within ±2% RH. That’s tight. In one case, a pharmaceutical lab in Melbourne had to shut down a study because a chamber fluctuated by ±1.8°C across shelves. The data was thrown out. No exceptions. Even a small drift can invalidate months of work.

What Counts as a “Significant Change”?

This is where things get messy. ICH Q1A(R2) says a product has failed if:

- Assay changes by more than 5%

- Any impurity exceeds its specification limit

- Physical appearance changes noticeably (color, texture, clumping)

- Functionality is lost (e.g., inhaler doesn’t spray properly)

But here’s the problem: there’s no clear rule on what “noticeably” means. One regulator might say a slight yellow tint is fine. Another might reject it. A Pfizer quality analyst shared on Reddit that a 4.8% drop in assay-still within 95-105% specs-was flagged as a failure. Why? Because it was the first sign of degradation. The regulator didn’t care about the statistical margin. They cared about the trend.

That subjectivity creates delays. Companies spend months arguing with inspectors. Some even run extra tests just to prove a change isn’t “significant.” It’s not science. It’s negotiation.

Real-World Problems and Fixes

Companies don’t always get it right. In 2021, Amgen got a warning letter because their monoclonal antibody product degraded during shipping. The standard 40°C test didn’t catch it. Why? Because the real issue was freeze-thaw cycles, not heat. The test didn’t simulate that.

Merck found a solution with Keytruda®. They ran intermediate testing at 30°C/65% RH and discovered a polymorphic transition-meaning the drug’s crystal structure changed. That affected how the body absorbed it. Without that test, they might have launched a drug that worked in Europe but failed in tropical climates.

Humidity control is another headache. In dry climates like Arizona, keeping 65% RH in a chamber means adding humidifiers. In humid places like Mumbai, it’s about removing moisture. One lab switched to dual-loop control systems and cut humidity variation from ±8% to ±3%. That’s the difference between passing and failing.

What’s Changing? The Future of Stability Testing

ICH Q1A(R2) is 20 years old. It was designed for pills and injections-not mRNA vaccines or antibody-drug conjugates. These new drugs are fragile. Heat, light, even shaking can ruin them. The current tests don’t capture that.

Some companies are already using predictive modeling. They run tests at 50°C, 60°C, even 80°C to speed up results. One study showed this can predict 24-month stability in just 3 months. But regulators are skeptical. The EMA rejected 8 model-based submissions in 2022-2023. They want real data.

The FDA is testing something new: real-time stability using process analytical technology (PAT). For drugs made continuously, this could cut testing time by half. If it works, it’ll change everything.

By 2030, McKinsey predicts 60% of stability data will come from models, not physical testing. But that’s still a long way off. For now, you still need the chambers, the data logs, the 36-month runs.

Getting It Right: What You Need to Do

If you’re developing a drug, here’s your checklist:

- Choose your target markets. That determines your long-term test condition (25°C or 30°C).

- Run accelerated testing at 40°C/75% RH for 6 months. If it fails, you need intermediate testing.

- Test at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months. Don’t skip early points.

- Calibrate your chambers. ±0.5°C and ±2% RH is non-negotiable.

- Document everything. Protocols, raw data, reports. The average dossier is 500 pages.

- Watch for trends, not just numbers. A slow drop in potency is more dangerous than a single failed result.

Stability testing is slow. It’s expensive. It’s repetitive. But it’s the last line of defense between a patient and a dangerous drug. There’s no shortcut. Not yet. And until there is, every hour in that climate chamber matters.

What are the standard temperature and humidity conditions for long-term stability testing?

The ICH Q1A(R2) guidelines define two standard conditions: 25°C ± 2°C at 60% RH ± 5% RH, or 30°C ± 2°C at 65% RH ± 5% RH. The choice depends on the intended market’s climate zone. For example, products for tropical regions use 30°C/65% RH, while those for temperate zones use 25°C/60% RH.

How long must accelerated stability testing last?

Accelerated testing must run for 6 months at 40°C ± 2°C and 75% RH ± 5% RH. This condition is designed to simulate extreme environmental stress and predict long-term stability. Results from this test help determine shelf life, but they must be supported by long-term data.

Is intermediate stability testing always required?

No, intermediate testing is only required if the long-term study is conducted at 25°C and the accelerated test shows a significant change. It’s performed at 30°C ± 2°C and 65% RH for 6 months. This helps bridge the gap between accelerated and long-term results, especially when the product’s behavior under stress is unclear.

What happens if a drug fails stability testing?

If a drug fails, the manufacturer must investigate the cause, halt distribution, and possibly recall the product. Regulatory agencies like the FDA can issue warning letters, block approval, or withdraw marketing authorization. In 2022, the FDA issued 27 such letters for stability-related issues. Failure can also lead to loss of consumer trust and financial penalties.

Are stability requirements the same for biologics and small molecule drugs?

No. Traditional ICH Q1A(R2) guidelines were designed for small molecule drugs. Biologics-like monoclonal antibodies or mRNA vaccines-are more sensitive to temperature, light, and mechanical stress. Standard 40°C tests may not detect degradation from freeze-thaw cycles or agitation. Regulators are working on new guidelines, but currently, companies must design custom stability protocols for these products, often going beyond ICH standards.

How do climatic zones affect stability testing?

Climatic zones determine the appropriate long-term storage conditions. Zone IVa (hot-humid) requires testing at 30°C/65% RH, while Zone IVb (hot-higher humidity) requires 30°C/75% RH. Companies targeting global markets must test under the most extreme conditions their product will face, which can add months to development timelines and increase testing costs.

Can predictive modeling replace physical stability testing?

Some companies use predictive modeling to estimate shelf life faster, running tests at higher temperatures (50-80°C). But regulators like the EMA have rejected model-based submissions when they lack real-world validation. While modeling may reduce testing time in the future, current standards still require physical data from real-time and accelerated studies. A hybrid approach-using models to guide testing-is the most accepted strategy today.

Melissa Melville

February 1, 2026 AT 04:51So basically, if your drug survives 40°C and 75% humidity for six months, you’re golden? Sounds like putting a chocolate bar in a sauna and calling it a quality control test.

Bryan Coleman

February 1, 2026 AT 08:31Been in pharma labs for 15 years. The ±0.5°C thing? Real. One time our chamber drifted 1.2°C and we had to toss 8 months of data. No joke. Calibration isn’t optional-it’s your reputation.

Sami Sahil

February 2, 2026 AT 04:54Bro in India here-our meds get baked in transit. We don’t test at 30/75 because we wanna. We test because our patients get broken pills. No one cares about the cost. They just want their medicine to work.

franklin hillary

February 4, 2026 AT 01:33Stability testing is the last silent guardian of public health. No one cheers for it. No one sees it. But when it fails, people die. And yet we still cut corners because ‘it’s expensive.’ We’re not just making pills. We’re making trust.

Nicki Aries

February 5, 2026 AT 03:47Let me tell you about the time a client insisted on using 25°C/60% RH for a product destined for Lagos. Three months in, the tablets turned to dust. The lab panicked. The regulator panicked. The patients? They just stopped taking it. I’ve seen this movie before. And it ends with a recall letter, not a happy ending.

It’s not about following the rules. It’s about respecting the people who’ll use this stuff. If you’re testing for Europe and shipping to Nigeria, you’re not being efficient-you’re being negligent. The ICH zones exist for a reason. Ignore them at your peril.

And don’t even get me started on biologics. A monoclonal antibody isn’t a pill. It’s a living molecule. Put it in a 40°C oven and you’re not predicting stability-you’re performing a necropsy. We need new frameworks, not just more chambers.

Every time a company says, ‘We’ll just run the accelerated test and call it good,’ I cringe. That’s not science. That’s gambling with someone’s life. And the worst part? It’s not even clever. It’s lazy.

There’s a reason the FDA issued 27 warning letters last year. It’s not because companies are evil. It’s because they’re overwhelmed. But we can’t outsource safety to wishful thinking. We need more funding, more training, more accountability.

And yes, the paperwork is insane. One dossier I reviewed was 872 pages. But every page? It’s a promise. To a child with diabetes. To an elderly person with hypertension. To someone who can’t afford to be wrong.

So next time you take a pill, don’t just swallow it. Think about the 36 months of data behind it. The sleepless nights. The calibrated chambers. The people who refused to cut corners. That’s what keeps you alive.

Ishmael brown

February 6, 2026 AT 03:06Whoa. So you’re telling me… we’re not just testing drugs… we’re testing fate? 😅

Aditya Gupta

February 6, 2026 AT 19:00Real talk: if you’re shipping meds to Mumbai and testing only at 25°C, you’re not a scientist. You’re a tourist with a lab coat.

Naresh L

February 7, 2026 AT 00:58It’s interesting how we treat stability like a math problem. But medicine isn’t just data points-it’s human experience. A tablet that holds its form in a lab might still crumble in the hands of a grandmother walking three miles in monsoon heat. We measure humidity, but do we measure hope?

Bob Cohen

February 7, 2026 AT 12:19Love how the industry calls it ‘stability testing’ like it’s some kind of yoga pose. Meanwhile, we’re basically forcing drugs into torture chambers to see if they’ll break. And then we act shocked when they do.

Nancy Nino

February 7, 2026 AT 19:58While I appreciate the thoroughness of this exposition, I must respectfully underscore that the implicit anthropocentric framing of regulatory compliance as a moral imperative, while rhetorically compelling, inadvertently obscures the structural inequities in global pharmaceutical access. The burden of compliance disproportionately falls upon low-resource manufacturers, yet the consequences of noncompliance are universally borne by patients. One cannot help but question whether the current paradigm truly serves equity-or merely sanitizes profit.

June Richards

February 8, 2026 AT 18:07Ugh. So we need to spend $2M and 3 years just to make sure a pill doesn’t turn into dust? I’m pretty sure my grandma’s aspirin from 2010 still worked fine. 🤷♀️